July 24, 2014

Interview with Kirk Nesset

by Caitlin McGuire

Kirk Nesset’s translations of Edmundo Paz Soldán’s poems, “Disappearances,” “Man of Fictions,” “In the Library,” “Pilar,” and “After the Breakup,” appeared in Fjords Review, Volume I, Issue 3.

Kirk Nesset’s translations of Edmundo Paz Soldán’s poems, “Disappearances,” “Man of Fictions,” “In the Library,” “Pilar,” and “After the Breakup,” appeared in Fjords Review, Volume I, Issue 3.

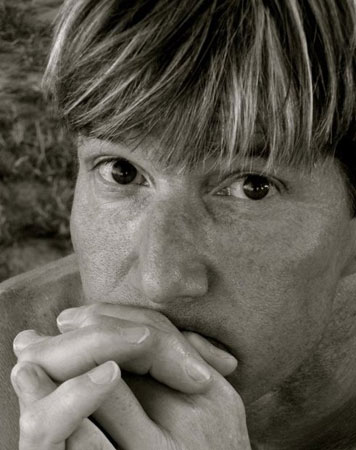

About Kirk Nesset

Kirk Nesset is author of two books of short stories, Paradise Road (University of Pittsburgh Press) and Mr. Agreeable (Mammoth Books), two books of translations, Alphabet of the World: Selected Work of Eugenio Montejo (University of Oklahoma Press) and Disappearances: Stories by Edmundo Paz Soldan (Calypso Editions), and a nonfiction study, The Stories of Raymond Carver (Ohio University Press); his book of poems, Saint X (Stephen F. Austin State University Press), appeared in 2012. His stories, poems and translations have appeared in The Paris Review, Southern Review, Kenyon Review, Gettysburg Review, Ploughshares, Crazyhorse, Prairie Schooner and elsewhere, including four of Norton’s anthologies - Flash Fiction Forward, Flash Fiction International, New Sudden Fiction and Sudden Fiction Latino. He was awarded the Drue Heinz Literature Prize, a Pushcart Prize and the Perry Poetry Prize, as well as grants from the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts. He teaches creative writing and literature at Allegheny College, and serves as fiction writer-in-residence at Black Forest Writing Seminars (Freiburg, Germany).

Kirk Nesset is author of two books of short stories, Paradise Road (University of Pittsburgh Press) and Mr. Agreeable (Mammoth Books), two books of translations, Alphabet of the World: Selected Work of Eugenio Montejo (University of Oklahoma Press) and Disappearances: Stories by Edmundo Paz Soldan (Calypso Editions), and a nonfiction study, The Stories of Raymond Carver (Ohio University Press); his book of poems, Saint X (Stephen F. Austin State University Press), appeared in 2012. His stories, poems and translations have appeared in The Paris Review, Southern Review, Kenyon Review, Gettysburg Review, Ploughshares, Crazyhorse, Prairie Schooner and elsewhere, including four of Norton’s anthologies - Flash Fiction Forward, Flash Fiction International, New Sudden Fiction and Sudden Fiction Latino. He was awarded the Drue Heinz Literature Prize, a Pushcart Prize and the Perry Poetry Prize, as well as grants from the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts. He teaches creative writing and literature at Allegheny College, and serves as fiction writer-in-residence at Black Forest Writing Seminars (Freiburg, Germany).

CM: How did you come across Edmundo Paz Soldán's writing?

KN: I heard him read at Allegheny College, where I teach, and I found his fiction compelling. This might have been eight or nine years ago. We talked that evening at a party at a colleague’s house. What a charismatic, generous, deep-thinking person, I thought. I began reading his work, the short stories especially. A year later, an editor at W. W. Norton wrote to ask if I had any translated flash to submit for an upcoming anthology. I didn’t, but soon afterwards did: pieces by Luisa Valenzuela, Juan Jose Saer, Eduardo Galeano and others. One of the others was a younger, less known but very talented Bolivian writer, Edmundo Paz Soldán. His story “Counterfeit,” as it is titled in English, was chosen for Sudden Fiction Latino.

CM: Name a place you've written about but never been.

KN: I wrote a poem this summer about the final days of Oliver Hazard Perry, the American naval commander who defeated the British in the Battle of Lake Erie. He sailed up the Orinoco River on a diplomatic mission into what is now called Venezuela, and caught yellow fever and died coming home. I spent six weeks reading and researching before I wrote those twenty-four lines. Biographies, journals, letters, newspapers, history, geology, geography, scientific data about period flora and fauna, and so on.

KN: I’m working on a story now set in Tallinn, Estonia’s capitol city. A different matter altogether, this is. I’ll need to visit the country to finish the story, I’m thinking.

CM: What do you consider the biggest struggle in translation?

KN: Making the thing float in English. Making the poem a poem or the story a story. A translator needs to be both a translator and an experienced writer. A fully bilingual, highly learned mind does not a poem or story make, necessarily. The most accurate, painstakingly faithful transcriptions are just that—transcriptions, not translations. They’re not stories or poems. They’re servile. We’ve all seen them. Some of our most cherished epics, even, have been crucified thus. Exquisitely precise, true to a fault to the material, intricately footnoted. They don’t breathe or shimmer or risk volatility, that ambiguous dance that makes poetry poetry. In the worst cases, they’re colorless or clunky or both.

KN: The translated piece in the end should be as correct as it can possibly be, even if correctness means compromising slightly or more than slightly. Even if it means moving away from the original for the sake of musical and compositional unity and of emotional resonance. The ideal translator should combine, as Donald Frame says, the learned humility of the good scholar with the imagination and daring of a gifted verbal artist working in poetry as well as in prose. Which is to say translating isn’t solving a puzzle. It’s not just transplanting and refiguring grammar. It’s about release and reentry. The fiber of thinking constituting the piece isn’t fiber you were born or grew into, usually. The rhythms aren’t rhythms you had thought possible, given your home base in language. So you move into the piece, the story or poem, tantalized, letting its thinking think thoughts your mind really can’t think, or couldn’t before, and now does somehow, and you feel its strange rhythms and try on its tones—and returning, hope to transmit it and make it your own. By transporting the goods from one world to another you transport yourself. There’s almost no better way of emptying yourself, of letting something or someone get into your skin.

CM: Name the greatest lesson you learned in school.

KN: The lesson of not giving up. Of sticking with something. Of getting the words down, the work done. I had a teacher in eighth grade who’d beat our butts in front of the class if we came to school without homework, or with homework unfinished. This created strong incentive to finish. I only got paddled once. Once was enough.

What is your favorite word in Spanish? In English?

KN: That’s a difficult question. As writers we tend to be in love with and enchanted by language. Words are the be-all and end-all. Words are uncanny, at times strange and surreal. They’re the building blocks of this thing we often blithely and mistakenly call “reality.” Ideas and understanding count for something, yes, but words matter more, along with the music of their arrangement. New favorite words bubble up every hour. How to narrow it down?

Híjole.

Nectarine.

CM: What was the last so-good thing that made you glad to be an artist?

KN: In May my sixth book was accepted by Calypso Editions (NYC). A book titled Disappearances, a gathering of translated microficciones by Edmundo Paz Soldán. We’re hoping the book will appear late spring or summer.

CM: What are you currently working on?

KN: At the moment I am finishing a manuscript of flash fiction, a bizarre, inspired book-to-be I’m calling Burn. I am also banging together what seems to be a novella, an eighty or ninety page something-or-other that may join a small constellation of old and new stories, all of which I hope to call the next book-to-be.