August 20, 2015

An Interview with Stephanie Dickinson

Conducted by Kristina Marie Darling

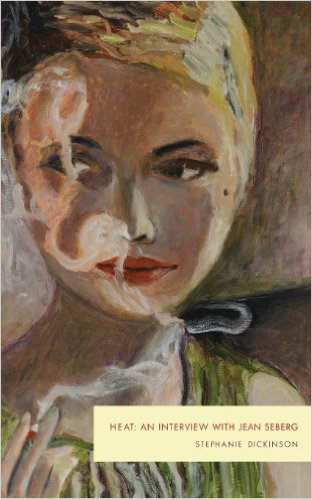

Stephanie Dickinson, an Iowa native, lives in New York City. Her novel Half Girl (winner of the Hackney Award) and novella Lust Series are published by Spuyten Duyvil, as is her recent novel Love Highway, based on the 2006 Jennifer Moore murder. Other books are Corn Goddess (poetry), Road of Five Churches (stories), and Port Authority Orchids (a novel-in-stories for young adults). Her writing appears in Hotel Amerika, Mudfish, The Dirty Goat, Cream City Review, Green Mountains Review, Quiddity, Fjords, and Water-Stone Review, among others. Her story “A Lynching in Stereoscope” was reprinted in Best American Nonrequired Reading. “Love City” and “Lucky Seven and Dalloway” were chosen for inclusion in New Stories from the South, the Year’s Best. Her work has received multiple distinguished story citations in the Pushcart Anthology, Best American Short Stories, and Best American Mysteries. Heat: An Interview with Jean Seberg, was released in 2013 by New Michigan Press.

Stephanie Dickinson, an Iowa native, lives in New York City. Her novel Half Girl (winner of the Hackney Award) and novella Lust Series are published by Spuyten Duyvil, as is her recent novel Love Highway, based on the 2006 Jennifer Moore murder. Other books are Corn Goddess (poetry), Road of Five Churches (stories), and Port Authority Orchids (a novel-in-stories for young adults). Her writing appears in Hotel Amerika, Mudfish, The Dirty Goat, Cream City Review, Green Mountains Review, Quiddity, Fjords, and Water-Stone Review, among others. Her story “A Lynching in Stereoscope” was reprinted in Best American Nonrequired Reading. “Love City” and “Lucky Seven and Dalloway” were chosen for inclusion in New Stories from the South, the Year’s Best. Her work has received multiple distinguished story citations in the Pushcart Anthology, Best American Short Stories, and Best American Mysteries. Heat: An Interview with Jean Seberg, was released in 2013 by New Michigan Press.

1. Where and how did Heat: An Interview with Jean Seberg begin?

SD: The seeds for Heat: An Interview with Jean Seberg were planted in my Midwestern adolescence. I grew up on an Iowa farm 3 miles from the nearest town, whose population was 100. I was convinced that nothing exotic, glamorous, or mysterious could take root in black soil furrow country, which seemed all tractor chug and chore boots. My mother disabused me of that notion when she casually mentioned that the movie star, Jean Seberg, had been Iowa-born and bred. Her home in Marshalltown, Iowa was only 60 miles from our farm. Later, it would surprise me that my mother, who was celebrity-adverse and uninterested in what passed for popular culture (she did not allow television in the house as she wanted her children to read), knew the legendary story of Seberg being chosen by director Otto Preminger out of 18,000 hopefuls to play Joan D’ Arc in his movie Saint Joan. This is the creation myth/the ur-story that followed Seberg throughout her life and embedded itself in legend—the sweet girl from Marshalltown before she became a monster. I learned from the Cedar Rapids Gazette Sunday supplement Parade that Jean Seberg lived in Paris and acted mainly in foreign language films, that she held radical political views, that she’d married Frenchmen—one a handsome party boy, one a brilliant writer—and then shed them; thereafter, I soaked up any random mention of the actress. Imbued in mystery, drenched in the exotic, I wondered how she had managed to transform herself from a small town Iowa girl into an international film star. I wanted to know more. For better or worse, Amazon still loomed in the future when a mouse click would order me her biography. In my rush to live larger after I left Iowa, I forgot to remember Jean Seberg, and when the Breathless actress took her own life, it somehow passed me by.

2. If you could tell readers only one thing before they opened Heat: An Interview with Jean Seberg, what would you want them to know and why?

SD: A close friend said of Jean Seberg, “She was always a kind of Alice for me. Even at the end when she was Alice in Horrorland.” Those two sentences explain much about the Seberg enigma. Meaning that the qualities strongly associated with the character of Alice in Alice in Wonderland, i.e. curiosity, kindness, intelligence, courtesy, and a sense of justice and wonderment, are the same qualities one associates with Seberg. She displayed them not only as a Breathless ingénue but in her “has-been” years when some regarded her as an alcoholic nymphomaniac. As her personality disintegrated, Seberg still approached life with a sense of wonderment. Awe and surprise. Think of Jean Seberg as a kind of Alice, I would tell readers before opening Heat. She’d actually experienced the rabbit hole. Jean Dorothy Seberg was a woman cleaved by the forces of repression and those of liberation, of artistry and addiction, a twin consciousness inside one head. Even her name harnesses the t-shirt Jean to the gingham Dorothy. Raised on a quiet street, it was almost as if the actress had been immaculately conceived of this teacher/housewife/mother and druggist/father. Her parents lived by Midwestern values, and while generous and intelligent, neither would have scribbled the fat blue crayon of dissent over their arms—tiny blue leaves, fingerprints, not one identical. Neither parents nor townspeople would have served Black Panthers their breakfast of poolside scrambled eggs and muffins, or worn billowing white robes to dive through the water’s aquamarine surface into the filthier depths. Wonderment. That is the one word, I would hold out to readers.

SEBERG: I’m the most unlikely of film stars. Look at my parents. When the hot tears of rain scald the clouds and trickle down their faces, they still call it a sunny day. Overcast is my favorite weather. I order vodka, three of them. Josephine Baker stealthily enters from back stage, wearing ostrich feathers and a fan. If I drink enough I glimpse her bare toed, ass-bucking dance of lush palm trees.

3. Your use of form in this collection is innovative and engaging. Because the book actually takes the form of an interview, you subvert readerly expectations in numerous ways, offering lyricism and aestheticized language in places where the reader likely wouldn't expect to find it. How did you arrive at the interview format, and what did this form make possible within the manuscript?

SD: I had seen Kate Braverman’s treatment of Marilyn Monroe in “The Collective Voice of Los Angeles Speaks: Marilyn Monroe,” in which she uses the interview format to question the mythical actress and her relationship to Los Angeles. I’m a great admirer of Braverman’s work and her Lithium for Medea, Palm Latitudes, and Small Craft Warnings are on my personal favorites’ shelf. I find her imagery luxuriant and layered, and her portrayal of Los Angeles as a city of corruption garbed in the feathers and flowers of paradise, riveting. I’d recently finished a hybrid collection entitled Lust Series published by Spuyten Duyvil, a series of 60 vignettes evoking sense of place and worlds, unmoored girls undone by beautiful and terrifying human acts. I’d begun work on a Seberg series when I read Braverman’s “The Collective Voice.” It inspired me and I knew I had to interview Jean Seberg; I had to question her about her relationship to the heartland Midwest. I wanted to experiment with the use of lyrical language in a form generally accustomed to more staid discourse. I hoped to evoke Jean, who symbolized for many the Midwest, who embodied the pre-Feminist beginnings of liberation, and free spiritedness. I wanted to see if I could keep expressive momentum going. I came to realize what an active form the questioner assumes in the back and forth of an interview, even or especially a fictional one. A tension develops between the question/answer roles as the questioner is able to ask the most incisive and personal interrogatories while revealing nothing of the self. Ultimately in Heat, the questioner assumed a larger role as the interview became the twin streams of the Seberg personality in a dialogue with the other. Almost a self-interrogation. I’d been fascinated by a video interview Seberg gave in the early 1960s to a French interviewer. Seberg answers the hard-edged questions (“Are you in psychoanalysis?” “Have you ever been?”) in French. Her melodious voice, her gamine quality, and exuberance all on display.

*

The form made possible skipping in chronological time between core moments, often without connective tissue; an approach that in a straight essay or fiction might have appeared scattershot. Seberg’s intellect hardly needed to be proved, as it was apparent in her command of four languages, but her quicksilver personality—unable to contain the twin streams of naiveté and sophistication, of generosity and narcissism, of repression and sexual frenzy that ran through her—called out for exploration. After Heat: An Interview with Jean Seberg morphed into a self-examination I could ask about 1962 when Seberg was pregnant by the still-married French writer Romain Gary, whose spouse refused to divorce him. In 1962 Hollywood, an unmarried pregnant actress could look forward to scandal and career disaster. Seberg kept the birth of her son Diego secret from her parents until he was two years old. In 1962 Hollywood, directors would hunt starlets like wild boars after truffles, but if a girl became pregnant, studio secretaries scheduled abortions between photo shoots. Not a word would touch the public. Seberg and Gary hid the birth of their son until they were able to wed.

*

The trees in 1962 hid a collective adultery and amnesia. The fictional interview form allowed me to pierce that amnesia with questions like—

Q: When you acted with Sean Connery who walked around nude in his dressing room, the scene in which you and Connery splash about in the hot tub, you insisted on a body stocking. How do we reconcile that with “a sexually insatiable woman,” words spoken by your second husband, Romain Gary?

Q: Talk about the last live-in lover, the almost-husband, Hasni.

I’d fallen for his uncle’s cooking at Le Medina, but love’s not possible on an earth that has no room for plants and animals. Yet I’m digesting the musk and lemon of his dark scent and imagining the room without him in it. He’s a bad boyfriend to have, not the shiny dime all the girls want to die for. He’ll rape Rue du Bac after I’m gone, sell all my paintings, and when I disappear in the night wearing only a sheet, taking the car keys, a fresh bottle of sleeping pills and mineral water, he reports me missing two days later. I’ll be disappearing, and reappearing, no thanks to him. He’s always had copies of my keys. Now he jingles my key ring. Opens a pastry box and shows me crème bruelle a voluptuous baked caramel cream cake. “You don’t seem to be eating, Jean. No one wants too stringy a chicken.” He thinks I can afford to feed him better. Feed him De Pio silk mid-calf socks.

4. In this collection, you have crafted a convincing persona, which arises out of both careful research and your own imaginative work. What unique possibilities does this kind of archival research open up within literary writing? What advice do you have for writers who are interested in engaging archival material?

SD: As researchers, we have more available in a single goggle search than our forebears did after decades in the stacks and card catalogues. Google Jean Seberg, and see how she’s been given a second life on the Internet: you can hear interviews of her musical voice speaking French and Italian and English; you can watch trailers of Lilith and Bonjour Tristesse; and there’s Seberg’s interview with Mike Wallace, as well as a grainy video of Otto Preminger coaching his discovery—the innocent from Marshalltown. What you won’t be able to find are trailers of the many European B-flicks she acted in or the R-rated movie Birds of Peru that her husband-director fashioned for her. You can’t watch those public stonings and humiliations. There are contemporary fashion blogs featuring photos of Jean Seberg’s Breathless style. I can devour blogs discussing the FBI surveillance of Seberg, visit websites devoted to famous suicides where Jean’s is featured, being especially titillating and gruesome. At our particular moment in epochal time, writers are attempting to bridge the great divide between print and digital worlds. We are synthesizing emails and text messaging into our written works, developing the email template as though the diary form of the 19th century, we are deciding about how and where to publish, weighing the pressure on our shared language from text messaging (will it flatten our budding Nabokov’s?). The information explosion on the web presents us with mindboggling archival footage. There’s an interest in the interview format within the contours of the Internet. The interview has transmigrated from the heard (radio, TV, video) onto the electronic page. The interview format seems particularly apt when our attention spans are said to be so short we may fall asleep before the end of a sentence if it’s too long. The question and answer, the direct in and out, the meats without the bread, the jelly-filling only, are more to our taste.

*

There are still only two biographies of Jean Seberg available on Amazon. Compare that to the vast literature on Marilyn Monroe. When I began delving into Seberg’s life I had access to my Iowa roots, and at my fingertips I had the world via the Internet. When I research I don’t make my goggle questions too specific, I start collecting pieces of raw data, letting the hunt begin organically, whimsically even. Often sites reproduce the same information if the search question is too specific. I enjoyed viewing Seberg from the vantage point of Otto Preminger or through the eyes of Romain Gary. I donated 50 copies of Heat: An Interview with Jean Seberg to the Jean Seberg International Film Festival held each November, the month of Seberg’ s birth. I’d sent one copy to the festival’s promotors, who passed it on to the academics organizing the roundtables, and they’d invited me to the festival. Although I couldn’t go, I was pleased to learn that Jean’s sister Mary Ann and her brother each received a copy.

I am presently working on a sequence of hybrids from the point of view of the Expressionist poet, Georg Trakl. I’m researching not only his storied relationship with his sister, his drug use, but his four-month service in WWI. While there are biographies of Trakl written in German, I’ve located no biographies translated into English. Except for the introductions in his poetry volumes, and a handful of essays, some beautifully written, there’s little information that goes into detail. I’m just now beginning the hunt.

5. IHow does your work in other genres inform your fiction? What are the most exciting things to borrow, steal, and adapt from types of writing other than literary fiction?

SD: I’m not a food writer or travel narrative writer, but I’ve written novels, poetry, short story collections, young adult stories, and I recently finished Girl Behind the Door: A Memoir of Delirium and Dementia. I am a writer with few readers. I am hoping to someday write a retro-thriller, determined to write a book that people will enjoy, rather than tell me my work is too dark, (disturbing, depressing) or who knows what but they had to put it down after a few pages. Plot is important and it’s heartening to learn that Shakespeare borrowed plots from Italian operas for his plays of genius. Thrillers aren’t my first or second love but I read them. I want to see how their plots function, how the story line succeeds or fails, how the reader is propelled from page to page, and how the writing and characters support the plot. I love language and thrillers aren’t where you go for beautiful language, yet some are very stylistically sophisticated. On the other side of the borrow, steal, and adapt spectrum are websites devoted to flora and fauna, i.e., the habits of wildlife, the insects of the Ukraine, sites devoted to sepia photographs of the workhorses and mules drafted into World War, indexes of photographs of the indigenous Plains people. I find lists inspiring, scientific descriptions of biological and geological processes—all a lovely fodder (adding texture, context) for writing. I have a fish encyclopedia written in the language of angels. The naming of the species inhabiting our planet seems an ethereal art. Consider the heartbreaking beauty of Even the ever growing lists of extinct species. The fodder is everywhere, so much raw material, it’s overwhelming.

*

Last year my novel Love Highway was published by Spuyten Duyvil. It takes its form from the true crime genre. July 25, 2006. The night drew me since first seeing Jennifer Moore’s picture on the New York Daily News cover. Teen Missing after Night of Underage Drinking. Her face appeared as if born underwater of the half-fish, half-human species, staring as if she’s looking over your shoulder at the sea’s floating world. It’s a mysterious face, her smile bewitching. Two days later the teen’s body was found in a dumpster and a pimp and prostitute were under arrest. The photo of the alleged perpetrator, Draymond Coleman, was tucked inside the paper while Krystal Riordan’s sad-eyed mug shot, emblazoned the newspaper’s cover. Hooker Watched boyfriend kill teen. Jennifer was abducted after a night of underage drinking and taken by Coleman, to a seedy Weehawken hotel room that he shared with his prostitute/girlfriend. Jennifer was raped and strangled while Riordan looked on. The entire evening had been one of poor judgment that began when Jennifer’s friend drove them in her mother’s car to Manhattan from New Jersey, to go clubbing. What should have been a teenage misadventure, an impulsive flirtation with the forbidden, led to ultimate consequences after the friend’s car was towed. This was the genesis of Love Highway, the collision of the different worlds inhabited by two young women close in age.

For three and a half years I’ve carried on a lengthy correspondence with Krystal, who is serving a 30-year-sentence at the Edna Mahon Facility for Women in Clinton, New Jersey. I discovered a more intelligent and sensitive young woman than I’d expected. Krystal had been an extremely talented basketball player in junior high school and yet while she had numerous opportunities to save Jennifer’s life, didn’t. I am outside in the free world and requests arrive from the locked world Krystal inhabits. Krystal’s friends mail me letters asking for small favors. “Can you make copies of the enclosed pics? One is my dad and daughter when she was a baby. (can you make four?). The other is my daughter with Santa this year. (can you make four copies of that as well?) So basically four copies of each would make my heart happy. Everyone comments on the cards you send me. They say I’m lucky. I make copies of bedraggled photographs for Krystal’s friends—the nameless pictures that come in stacks. Some are so old and taped they stick to the glass of the photocopy machine. Precious snapshots taken from the inmates’ free lives. The newest inmates have Facebook pages, the older inmates have MySpace pages, and the oldest have left no trace in the digital universe. I am asked to download welfare applications and low-income SSI applications. To find out how to rent an apartment in the Newark Gateway Building. To visit the Facebook pages of inmates’ friends and print photos. “No pictures with gang signs or middle fingers. You can color out hand signs with a marker.”