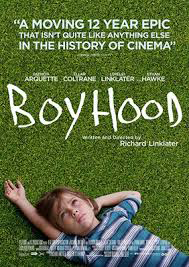

Directed by Richard Linklater, 2014

by Raqi Syed

November 06, 2014

In an interview with NPR discussing the genesis of his film Boyhood, Richard Linklater mentions that when he began to think about the story, he imagined writing it as a novel, even an experimental novel. This should come as no surprise as one of the most striking aspects of watching the movie is the feeling that the ebb and flow of life—the entire spectrum of the mundane through the dramatic—are somehow on equal footing.

In an interview with NPR discussing the genesis of his film Boyhood, Richard Linklater mentions that when he began to think about the story, he imagined writing it as a novel, even an experimental novel. This should come as no surprise as one of the most striking aspects of watching the movie is the feeling that the ebb and flow of life—the entire spectrum of the mundane through the dramatic—are somehow on equal footing.

It is not a coincidence that Carl Knausgaard’s “My Struggle,” also came to the attention of American audiences this year. At a time when visual effects has learned to solve the problem of the uncanny valley, to create digital humans so believable the mortality of real actors has ceased to be a problem, we remain interested in the actual mysteries behind real-time aging. Just as Knausgaard’s pseudo memoir covers in painstaking detail the life of a man from childhood to adulthood over the course of six volumes, in “Boyhood” we have the face a boy transforming over a period of twelve years, into a young man. The conceit of the film, which compels us to keep watching a three hour movie in which not very much happens, is the meta-narrative of realness. The visual arc of a face morphing in front us, like a digital trick, alongside the knowledge that it is in fact transforming and it is no trick other than the compression of time.

Mason is our hero and his quest is one of self-discovery. But it is not a quest that feels scripted. Of Linklater’s earlier films, Boyhood is perhaps most indebted to Waking Life. In both films narrative is supplanted by larger philosophical concerns such as human consciousness and where waking and dreaming overlap. Though it is very much a film that presents itself in the realist mode, Boyhood is most concerned with the way in which a young boy continues to dream even as he grows up.

In My Struggle, Knausgaard spends pages and pages discussing everything from corn flakes, a swimming cap, and fitting a key into a door lock in excruciating detail. So too does Boyhood linger upon the moments in between the big stuff of life. The scenes we spend with Mason spray painting graffiti in a tunnel, walking through the woods, and hanging out on an incomplete construction site are filled with a tension that never comes to bear. We learn as we watch Mason and his family that it is the cumulative effect of all the boring bits of life punctuated by the fleeting dramatic moments that adds up to a sense of a life fully lived. As moviegoers we have been conditioned to expect every tense moment in a film to lead to horror or tragedy. When Mason is looking at his phone and texting while driving, an impending car crash hangs in the air. We have been weaned onto a diet of the three act plot structure and page beats and character arcs based on the hero’s journey. But this is not that kind of story.

In My Struggle, Knausgaard spends pages and pages discussing everything from corn flakes, a swimming cap, and fitting a key into a door lock in excruciating detail. So too does Boyhood linger upon the moments in between the big stuff of life. The scenes we spend with Mason spray painting graffiti in a tunnel, walking through the woods, and hanging out on an incomplete construction site are filled with a tension that never comes to bear. We learn as we watch Mason and his family that it is the cumulative effect of all the boring bits of life punctuated by the fleeting dramatic moments that adds up to a sense of a life fully lived. As moviegoers we have been conditioned to expect every tense moment in a film to lead to horror or tragedy. When Mason is looking at his phone and texting while driving, an impending car crash hangs in the air. We have been weaned onto a diet of the three act plot structure and page beats and character arcs based on the hero’s journey. But this is not that kind of story.

Boyhood is a film that dares to depart from Hollywood plotting. It asks us to be patient. To sit through the scenes where the fate of characters remains murky. So that perhaps an hour later when all these characters have leapt through time and it’s five years later, the drama of the story reveals itself to us in a small quiet revelation, rather than the grand aha. Just as life really does.

East Villager Billy The Artist Climbs Atop Ai Wei Wei's Fence To Shine A Light On It

From Russia, With Love A review of SCREENS: A Project About “Community”

The Inner Strength of Joan Didion

Basquiat—The Unanswerable Answer to the Art World

May It Last: A Portrait of the Avett Brothers

Move Over Hogwarts—The Practical Magic Is at Headfort

The Dog Days of Summer—Two Ways to Beat the Heat

The Mistress, the Publisher, His Son & His Mother

Santoalla-- the Spaces Between

Reading Arthur Miller in Tehran, The Salesman

Killing the ISIS Propaganda Machine, City of Ghosts

Bewitched, Bothered and Beguiled, The Beguiled– A Film Review

A Spoonful of Sugar-- Not Saccharine The Big Sick: A Film Review

Fiona and the Tramp, Lost in Paris- a review

Movie Review: Beatriz at Dinner

Cameraperson, dir. Kristen Johnson: stories from behind the camera lens

SELFISH, Review by Heather Zises

Winter on Fire: Ukraine’s Fight For Freedom, dir. Evgeniy Afineevsky

Strange Days directed by Kathryn Bigelow (1995)

World of Tomorrow and the Quit-Bang Language of the Future

Quintet, Directed by Robert Altman, 1979

Classic Movie Short Review: Croupier (1998)

Popeye, Directed by Robert Altman, 1980

3 Women, Directed by Robert Altman, 1977