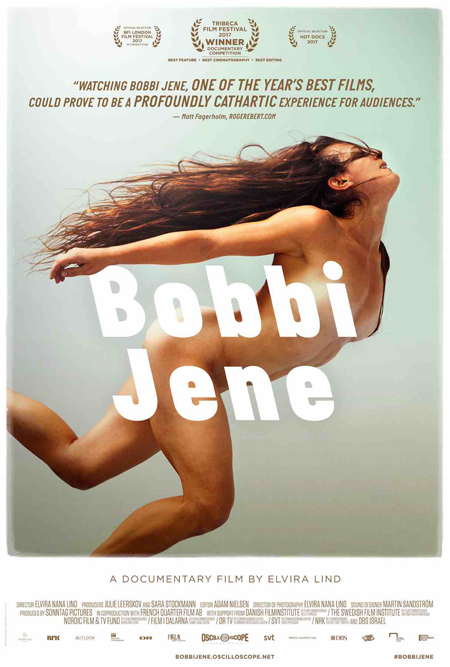

Bobbi Jene—

A Film Review by: Jennifer Parker

September 22, 2017

Bobbi Jene sees the possibility of a body in motion where others see a concrete wall. She finds inspiration for choreography in not what is mundane but what is foundational to modern human existence—to physical building materials that protect us. No wonder filmmaker Elvira Lind found a documentary worth making in the story of Bobbi Jene Smith. The film follows Smith’s odyssey from Batsheva dancer in Tel Aviv to respected soloist and choreographer in the US, as well as exploring how Smith’s personal life and background influence her work. Smith’s choreography challenges the conventions of how women are supposed to behave on stage. Admittedly, neither Bobbi Jene Smith’s process nor her choreography are easy to watch. After spending nearly one third of her life dancing for Naharin using his fundamental technique, Gaga, it is fruitless to separate the influences of Smith’s technique from her work. Certain performances are off limits to her parents. There’s a now infamous piece involving a sandbag and an enviable orgasm—a metaphor for effort and pleasure. The dance challenges perceptions of female bodies and sexuality—what it means to be vulnerable and what it means to move walls.

Bobbi Jene sees the possibility of a body in motion where others see a concrete wall. She finds inspiration for choreography in not what is mundane but what is foundational to modern human existence—to physical building materials that protect us. No wonder filmmaker Elvira Lind found a documentary worth making in the story of Bobbi Jene Smith. The film follows Smith’s odyssey from Batsheva dancer in Tel Aviv to respected soloist and choreographer in the US, as well as exploring how Smith’s personal life and background influence her work. Smith’s choreography challenges the conventions of how women are supposed to behave on stage. Admittedly, neither Bobbi Jene Smith’s process nor her choreography are easy to watch. After spending nearly one third of her life dancing for Naharin using his fundamental technique, Gaga, it is fruitless to separate the influences of Smith’s technique from her work. Certain performances are off limits to her parents. There’s a now infamous piece involving a sandbag and an enviable orgasm—a metaphor for effort and pleasure. The dance challenges perceptions of female bodies and sexuality—what it means to be vulnerable and what it means to move walls.

Iowa born and raised, Smith was a dance recital kid—the film shows pictures of her in full sparkly dance costume complete with glittery makeup. Glitz to Julliard isn’t an organic path. It takes more than a little bit of talent. Classical ballet training made its way into her DNA. From Julliard to Ohad Naharin’s Batsheva dance company was a cocktail of the impulsiveness of youth, grit, facility and the ability to obtain a passport. After seeing Batsheva dance in New York, Smith thanked Naharin for bringing his company to Julliard. She knew immediately that she wanted to dance with Batsheva. Naharin said to move to Israel. With one year left at Julliard, Smith got a passport and left the United States for the first time in her life.

Bobbi Jene talking with mentor and artistic director of Batsheva Dance company, Ohad Naharin.

Photo courtesy Oscilloscope Laboratories

There’s a marvelously intimate scene at the beginning of the film where Bobbi is telling Ohad that she is leaving Batsheva at the end of the season. Like seeing lovers who no longer have a spark but maintain a deep respect, it is almost like watching a breakup scene in a romcom minus the schmaltz. He delicately picks remnants of foods off her plate, looks like he’s on the edge of tears. She looks perpetually frozen in late adolescence with impossibly long hair, delicate facial features and a powerful body. She is turning thirty and Ohad who was about sixty-two at the time, tells her it shouldn’t bother her. His face scarcely betraying his age---not exactly handsome but oh-so-sexy. An Israeli man who has seen both the battlefield and the ballet barre--full head of hair, dancer’s body, just enough lines on his face, empathic and straight. He’s a choreographer who doesn’t fetishize prepubescent looking women. He loves the female form and celebrates it in dance. Naharin, himself the subject of a documentary, Mr. Gaga, understands her drive to create.

Bobbi Jene performs her solo piece at The Israeli Museum in Jerusalem

Photo courtesy Oscilloscope Laboratories

It’s almost thirty minutes into the film that we become aware that we’re watching a documentary—the moments captured serendipitously intimate. Even the lighting cooperated. Bobbi says to the filmmaker that she and Ohad were lovers, that he taught her the difference between pain and pleasure and effort and pleasure and they are like a switch. Had it not been for this moment, I’m not sure how long it would take the audience to realize that they are watching a documentary. Director, Lind, has a knack for capturing Smith’s most poignant moments and for creating a cogent arc within the structure of her film. It takes a certain type of filmmaker who can make her audience forget they are watching a documentary for most of the film that allows us to reconcile being so intimate with her subject without feeling voyeuristic.

Bobbi Jene rehearsing with Batsheva Dance Company in Tel Aviv

Photo courtesy Oscilloscope Laboratories

Watching Bobbi Jene struggle with life choices, to move hundreds of pounds of bricks to understand desired movements and then to share them, often naked and vulnerable is something only a woman who feels secure in her femininity while simultaneously confident in her strength and character can do.

Bobbi Jene

Run time: 95 Minutes: Not Rated (Mature Content)

Oscilloscope Laboratories

Opens September 22, 2017

From Russia, With Love A review of SCREENS: A Project About “Community”

The Inner Strength of Joan Didion

Basquiat—The Unanswerable Answer to the Art World

Let’s talk about the hard stuff: Get Out

3 Women, Directed by Robert Altman, 1977

May It Last: A Portrait of the Avett Brothers

Move Over Hogwarts—The Practical Magic Is at Headfort

The Dog Days of Summer—Two Ways to Beat the Heat

The Mistress, the Publisher, His Son & His Mother

Santoalla-- the Spaces Between

Reading Arthur Miller in Tehran, The Salesman

Killing the ISIS Propaganda Machine, City of Ghosts

Bewitched, Bothered and Beguiled, The Beguiled– A Film Review

A Spoonful of Sugar-- Not Saccharine The Big Sick: A Film Review

Fiona and the Tramp, Lost in Paris- a review

Movie Review: Beatriz at Dinner

Cameraperson, dir. Kristen Johnson: stories from behind the camera lens

SELFISH, Review by Heather Zises

Winter on Fire: Ukraine’s Fight For Freedom, dir. Evgeniy Afineevsky

Strange Days directed by Kathryn Bigelow (1995)

World of Tomorrow and the Quit-Bang Language of the Future

Quintet, Directed by Robert Altman, 1979

Classic Movie Short Review: Croupier (1998)