Fiction

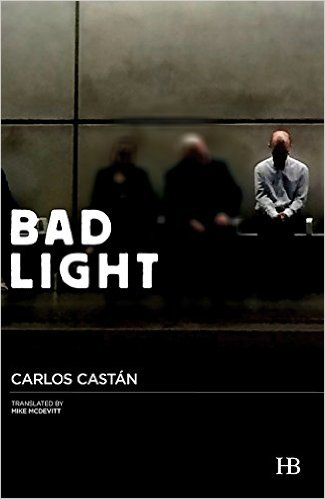

Bad Light

by Carlos Castán

Translated by Michael McDevitt

Hispabooks, 2016

200 pages

ISBN 978-8494365850

by Sandy Rodriguez Barron

In Bad Light, a man sets out to find out who murdered his best friend. Set in Zaragoza, Spain, the novel begins with a question--who would want to kill a sweet, lonely guy like Jacobo? The police find no clues, no witnesses. Weeks go by and there are no suspects. So the structural façade of the novel is clearly a crime mystery, and even if you know that Castán is a literary writer, it would be reasonable to expect some of the standard devices of the genre: investigation, police procedure, forensic analysis, deductive reasoning, tense confrontations and at least one action-packed scene. But to Castán, the puzzle surrounding the murder of Jacobo is subordinate to the existential questions that his death poses. Castán’s intense literary style reflects his advanced studies in philosophy; his prose is dense with serious reflection, poetry, weaving his words with those of writers and thinkers such as Primo Levi, Marguerite Duras, Emil Cioran, and Paul Celan. Bad Light is chock-full of lines to be underlined about love, literature, art, loneliness, friendship, death, and old age, and it takes the form, for most part, of interior monologue. Castán seems to anticipate some discontent in this regard, because he defends his aesthetic choice right within the text of the novel: “I’ve always preferred an interior monologue over convoluted stories that unfold amid revolvers, bona fide clues and red herrings, enigmas and alibis.” So Bad Light admittedly doesn’t concern itself much with with the shell games of contemporaries such as Dennis Lehane or Stieg Larsson; it’s more about the thoughts and emotions that Jacobo’s murder evokes for the narrator.

The story of Jacobo’s tragic end is told by a man who is utterly destroyed by his recent divorce. “Still bearing the imprint of a wedding band”, the narrator moves to Zaragoza, where he meets Jacobo in a smoke-filled neighborhood bar. Jacobo is similarly untethered by the failure of his marriage, and the two men commiserate and bond over their mutual love of books, music, art, and travel. Jacobo is particularly fond of telling exaggerated tales of past sexual adventures. Hermetic and lonely, Jacobo begins to collect an arsenal of knives and weapons that he keeps near the entrance of his apartment, and lives in a worsening paranoid state over nameless, shadowy executors out to get him. So when Jacobo is found dead and riddled with knife wounds inside his apartment, it becomes obvious that Jacobo wasn’t so delusional after all. A few weeks later, the narrator uses his spare key to enter Jacobo’s apartment and rummages through his belongings in search of clues. Castán takes his time here, using the solitude of Jacobo’s empty apartment to contemplate the resonant meaning of objects, especially books. “Every library, no matter how personal, is arranged as if on display. It craves admiration, the simple recognition of a like-minded soul or a polar opposite. This is not altogether uncalculating, for it is, when all is said and one, a language. And as such it may be heartfelt or duplicitous.” Throughout the novel, the relationship between belongings and identity is deeply explored. One of the most unique contemplations is the narrator’s response to seeing himself—his happiness, his promise, his innocence--in childhood photographs: “The sight of that boy arouses in me a tenderness I find hard to sustain. I look at that boy and my heart goes out to him. Child, forgive me for all the harm I’ve inflicted on you, for what I have ended up making of your life. Forgive me for not having listened to you more. For not having spent more time with you. I have ruined the life of no other creature as I have yours.”

Hacking into Jacobo’s email yields a string of correspondence with a mysterious woman named Nadia, and here Castán shows his vast literary gifts by creating a love story about the absence of love, a lustful adventure twisted around a tragedy. Some of the novel’s best lines are about yearning and the agony of waiting, as in Jacobo’s emails to Nadia-- “There is a coin in midair, it’s been falling in slow motion for days now, and that’s what makes me tremble and implore who knows what gods not to let it fall on the side that condemns me to simply dreaming of you.” Nothing more can be said of Nadia’s role without giving too much away.

Each chapter is ultimately tied together by the abysmal loneliness of this man, this shadow, who has lost everything, a man disconnected and raw and completely lost. The miracle of Castán’s writing is his ability to bridge the gap between this deeply pessimistic soul and the reader, to make us empathize with his mistakes, even as he wades deeper into the dark waters of his own destruction. Up until a third of the way through the book, the reason behind his divorce is the single dramatic question, and it is perhaps the question most alluring to the female reader--the why, the how, and the desire to know more about this woman whose absence is so lethal. Castán brilliantly dodges our curiosity, and in lieu of answers, offers only shadowy glimpses, such as “a photograph of a woman in a picture frame that can barely stand upright.” Although Castán’s soliloquies are gorgeously poetic, excessive summary has its thorns, and it keeps us at a distance from the action and characters, which is the entire point Castán is trying to make. Some of us live in a dream state, while others are awake in the darkness, condemned to witness “the horror of the planets floating in the darkness of infinity and filling everything with a solitude too vast even for the universe to hold.”

A single line, hidden in plain sight, is the only predictor of the twist ending, which most will agree makes for a hasty retreat. The crime hook and rushed ending will seem gimmicky to his core audience, but without it some of us might have missed the opportunity to experience Castán’s strange and beautiful work. Perhaps it’s this line that best embodies the spirit of the novel and of the impulse behind storytelling itself: “I was also trying, clumsily, to get across that other idea of mine, as old as it is muddled, that every human life contains within it the story of its century.”

Fuel for Love by Jeffrey Cyphers Wright

Alexis Rhone Fancher’s Erotic: New and Selected Poems

Chasing Homer by László Krasznahorkai

Eight Perfect Murders by Peter Swanson

The Death of Sitting Bear by N. Scott Momaday

WHILE YOU WERE GONE BY SYBIL BAKER

MY STUNT DOUBLE BY TRAVIS DENTON

Made by Mary by Laura Catherine Brown

THE RAVENMASTER: My Life with the Ravens at the Tower of London

Children of the New World By Alexander Weinstein

Canons by Consensus by Joseph Csicsila

And Then by Donald Breckenridge

Magic City Gospel by Ashley M. Jones

One with the Tiger by Steven Church

The King of White Collar Boxing by David Lawrence

They Were Coming for Him by Berta Vias-Mahou

Verse for the Averse: a Review of Ben Lerner’s The Hatred of Poetry

Ghost/ Landscape by Kristina Marie Darling and John Gallaher

Diaboliques by Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly

Core of the Sun by Johanna Sinisalo

Maze of Blood by Marly Youmans

Tender the Maker by Christina Hutchkins

Conjuror by Holly Sullivan McClure

Someone's Trying To Find You by Marc Augé

The Four Corners of Palermo by Giuseppe Di Piazza

Now You Have Many Legs to Stand On by Ashley-Elizabeth Best

The Darling by Lorraine M. López

How To Be Drawn by Terrance Hayes

Watershed Days: Adventures (A Little Thorny and Familiar) in the Home Range by Thorpe Moeckel

Demigods on Speedway by Aurelie Sheehan

Wandering Time by Luis Alberto Urrea

Teaching a Man to Unstick His Tail by Ralph Hamilton

Domenica Martinello: The Abject in the Interzones

Control Bird Alt Delete by Alexandria Peary

Twelve Clocks by Julie Sophia Paegle

Love You To a Pulp by C.S. DeWildt

Even Though I Don’t Miss You by Chelsea Martin

Revising The Storm by Geffrey Davis

Midnight in Siberia by David Greene

Strings Attached by Diane Decillis

Down from the Mountaintop: From Belief to Belonging by Joshua Dolezal

The New Testament by Jericho Brown

You Don't Know Me by James Nolan

Phoning Home: Essays by Jacob M. Appel

Words We Might One Day Say by Holly Karapetkova

The Americans by David Roderick

Put Your Hands In by Chris Hosea

American Neolithic by Terence Hawkins

I Think I Am in Friends-Love With You by Yumi Sakugawa

box of blue horses by Lisa Graley

Review of Hilary Plum’s They Dragged Them Through the Streets

The Sleep of Reason by Morri Creech

The Hush before the Animals Attack by Carol Matos

Regina Derieva, In Memoriam by Frederick Smock

Review of The House Began to Pitch by Kelly Whiddon

Hill William by Scott McClanahan

The Bounteous World by Frederick Smock

Review of The Tide King by Jen Michalski

Going Down by Chris Campanioni

Review of Empire in the Shade of a Grass Blade by Rob Cook

Review of The Day Judge Spencer Learned the Power of Metaphor

Review of The Figure of a Man Being Swallowed by a Fish

Review of Life Cycle Poems by Dena Rash Guzman

Review of Saint X by Kirk Nesset