POETRY

Poetic Fuel

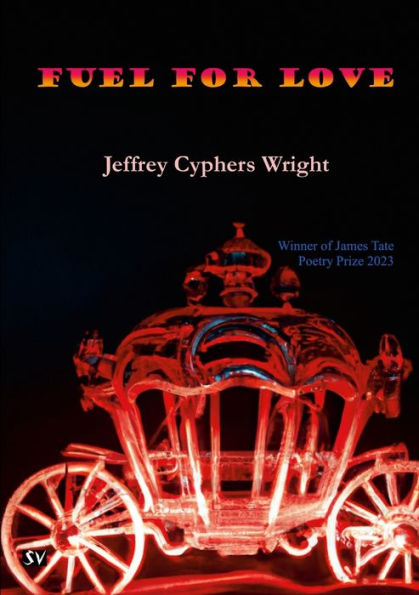

Fuel for Love

by Jeffrey Cyphers Wright

Page Count: 34 pages

SurVision Books (Dublin, Ireland and Reggio di Calabria, Italy)

ISBN:978-1-912-96345-4

Review by James Berger

October 03, 2024

Jeffrey Cyphers Wright’s new book–the latest of many: Fuel for Love. Everyone knows Jeff Wright–as editor-publisher-curator-impressario and poet. Go to any reading in New York south of 14th St or in Brooklyn and Jeff either has organized it, is reading in it, or just has showed up because he’s a friend of the readers. But amid all these guises and journeys, he is a real poet and a good one. He has a lineage. He studied with Allen Ginsberg, was a friend of Ted Berrigan, can be considered a third-generation New York Poet, a bit younger than Ron Padgett and David Shapiro. There’s something of Padgett (and through Padgett to Frank O’Hara) in his voice–his humor, his feeling for the city as a place of possibility, happenstance, and astonishment, his refusal to take life–his life–so seriously (and yet living it and acknowledging its entailments). His poems teeter on the precipice of the Serious, but maintain the discipline not to blunder into such an enjambment of no return. I think with Jeff, that discipline is called “wit.”

I’ll say two words about Fuel for Love: Sonnets and Puns.

All the poems in the book are sonnets (all thirty of them, a short book); or all but one. That is, they’re all fourteen lines (except for the one that is twelve). And that’s one definition of a sonnet, from Petrarch till now–some verbal fuel for love, poured into a fourteen line vessel. And these are energetic sonnets, sonnets at play, for they take many different forms. Four of the sonnets are in what we might call classic form... the Shakespearean sonnet of three stanzas of four lines each, plus a couplet at the end. Four sonnets reverse this form, having four stanzas of three lines plus a couplet. There are six sonnets composed entirely of couplets (seven couplets). And then there are fifteen sonnets in particular irregular forms: stanzas of 6-6-2 lines; 3-1-4-1-1-2-2; 4-3-7; 3-2-4-1-4; 5-5-4; 4-3-4-1-2.... You get the picture. Jeff’s friend and mentor, Ted Berrigan, of course wrote great sonnets, but Berrigan did not play with form like this. It seems to me that this is the most imaginative set of variations on the sonnet form since Philip Sidney’s astonishing performances in Stella and Astrophil in 1591, and even Sidney didn’t chop and stretch the sonnet the way that Jeff does. (Not to say that Jeff’s poems are better because nobody’s poems are better than Sidney’s, that is, at least as formal artefacts!).

This variation of stanzas within the sonnet form is both ingenious and purposeful. The stanza, for Wright, is a unit of thought and sound, or breath. Something of what Charles Olsen theorized concerning the poetic line as the essential sonic and semantic unit of a poem, Jeff does with the stanza. The variation of the stanzas is not random experiment; it follows from voice and meaning. There is enjambment of lines within stanzas, but never between stanzas. The stanza is a solid unit of thought and rhythm. As the poem breathes semantically, a pattern of stanzas is initiated. Here is the title poem, “Fuel for Love.”

Sundown drags some fiery slag into a gap

in the Jersey skyline. Day’s wick meets

the star trimmer and glides toward

the target area. Harvesting goodbyes.

Old statues vow to obey whatever

green habits they have donned. Shadows

of wigs weave through the parks’ limbs.

Windfall plums bruise the ground.

Our story, a road of half-used light.

Welcome to the hero you’ve squeezed

out of an antique compass.

Checking the mirror, our driver signals.

Now, cashing in the tokens of distance,

what we run on expands as it diminishes.

This is an impressive poem–its revision of sunset over the Hudson as a sort of volcanic irruption of light and substance–its “fiery slag.” And from there, we get an incessant experience of image, metaphor, and physical tongue-turning that arrives at an ending that rather gorgeously refuses to stay still or in one direction: “squeezed out of an antique compass,” which is very nice. And then, that driver who checks the mirror–that is, looks back behind him–and is that only physical or also temporal? I take it as both. And then the paradoxes of the closing couplet: How does one “cash in” on “tokens of distance”? Where are they? How would one possess such things, by definition elsewhere? And what is it that “we run on”? Is that the fuel of the poem? And how does it “expand as it diminishes”? The tokens of distance, the driver’s signal after checking the mirror; the impossible equilibrium of expansion and diminishment.

The title of the poem, and of the book, is, as is obvious, a pun. Fuel for love; fool for love. Or, by some air extension woven out, Food for Thought? Puns are important in this book; and the extensions or associations that may follow from them. The “fuel” is a “fool.” the fuel for love is folly. Or food. If music is the food of love? Or if folly is the food for thought? Or, if the fool would persist in his folly he would become love, or fuel? Or folly is what is consumed as love is reached? How much love is gained (or lost) per liter of folly?

In Fuel for Love, there are eighteen puns, including that in the title. This is in a book of thirty pages, one poem to a page. This seems to me a lot of puns for a book of this length. Puns seem to be a structuring, connective force in the book, a mode through which the poems think. We tend to put down puns. We groan at puns; we apologize for them (No pun intended, we say–and yet we do intend it!). They draw on chance, on mere sonic resemblance, rather than on the presumed deeper commonalities that instigate metaphor, the pun’s aristocratic cousin. But the good pun, the expansive pun allows and insists on its wider range of association that its randomness makes possible.

One more example: The book’s first poem, “The Quick Key,” ends with a couplet and a pun: “Razor-thin euphoria is a wake-up call./ The party is here–inside these cells.” These cells. The party is in a physical space–these cells; but is the party then in a prison, a monastery? But the first line referred to “euphoria,” so are the cells then biological cells, neurons? But then might not the “cells” also be components of the poem, stanzas? “Stanza” is Italian for “room.” Thus John Donne’s pun, “We’ll build in sonnets pretty rooms.” Yes, yes, and yes. The party is here. Euphoria and confinement; the mind as nutshell of infinite space; encountered and experienced through the poem’s formal arrangement. “The Quick Key,” which begins “Ever-shrinking path to glory’s kennel,” indicates already a relation between enclosed space (physical, neural, or aesthetic)—which may seem the opposite of glorious; a kennel, a cell– –and the possibility of some ecstatic release: glory or euphoria. And “cells” here is not a metaphor. It does not stand for some other meaning or coexist with some other meaning or point toward some other meaning adjacent to itself. It does not “carry across” to some other semantic place. No, it contains in itself disparate meanings that build on and conflict with each other. This is the richness of the pun that is central to Jeff Wright’s method of writing.

Perhaps, at last, the “fuel for love” is the poem itself: the conjoined acts of observation, feeling, and invention that connect consciousness to world–that apprehension of the fiery slag of sunset, the bruised fruit, the signal, the expanding-contracting nature of being in the world and using language and being in love with both. What folly, what fuel!

Oh, and I don’t know why the one poem has only twelve lines.

Fuel for Love by Jeffrey Cyphers Wright

American Neolitic by Terence Hawkins

Alexis Rhone Fancher’s Erotic: New and Selected Poems

Chasing Homer by László Krasznahorkai

Eight Perfect Murders by Peter Swanson

The Death of Sitting Bear by N. Scott Momaday

WHILE YOU WERE GONE BY SYBIL BAKER

MY STUNT DOUBLE BY TRAVIS DENTON

Made by Mary by Laura Catherine Brown

THE RAVENMASTER: My Life with the Ravens at the Tower of London

Children of the New World By Alexander Weinstein

Canons by Consensus by Joseph Csicsila

And Then by Donald Breckenridge

Magic City Gospel by Ashley M. Jones

One with the Tiger by Steven Church

The King of White Collar Boxing by David Lawrence

They Were Coming for Him by Berta Vias-Mahou

Verse for the Averse: a Review of Ben Lerner’s The Hatred of Poetry

Ghost/ Landscape by Kristina Marie Darling and John Gallaher

Enchantment Lake by Margi Preus

Diaboliques by Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly

Core of the Sun by Johanna Sinisalo

Maze of Blood by Marly Youmans

Tender the Maker by Christina Hutchkins

Conjuror by Holly Sullivan McClure

Someone's Trying To Find You by Marc Augé

The Four Corners of Palermo by Giuseppe Di Piazza

Now You Have Many Legs to Stand On by Ashley-Elizabeth Best

The Darling by Lorraine M. López

How To Be Drawn by Terrance Hayes

Watershed Days: Adventures (A Little Thorny and Familiar) in the Home Range by Thorpe Moeckel

Demigods on Speedway by Aurelie Sheehan

Wandering Time by Luis Alberto Urrea

Teaching a Man to Unstick His Tail by Ralph Hamilton

Domenica Martinello: The Abject in the Interzones

Control Bird Alt Delete by Alexandria Peary

Twelve Clocks by Julie Sophia Paegle

Love You To a Pulp by C.S. DeWildt

Even Though I Don’t Miss You by Chelsea Martin

Revising The Storm by Geffrey Davis

Midnight in Siberia by David Greene

Strings Attached by Diane Decillis

Down from the Mountaintop: From Belief to Belonging by Joshua Dolezal

The New Testament by Jericho Brown

You Don't Know Me by James Nolan

Phoning Home: Essays by Jacob M. Appel

Words We Might One Day Say by Holly Karapetkova

The Americans by David Roderick

Put Your Hands In by Chris Hosea

I Think I Am in Friends-Love With You by Yumi Sakugawa

box of blue horses by Lisa Graley

Review of Hilary Plum’s They Dragged Them Through the Streets

The Sleep of Reason by Morri Creech

The Hush before the Animals Attack by Carol Matos

Regina Derieva, In Memoriam by Frederick Smock

Review of The House Began to Pitch by Kelly Whiddon

Hill William by Scott McClanahan

The Bounteous World by Frederick Smock

Review of The Tide King by Jen Michalski

Going Down by Chris Campanioni

Review of Empire in the Shade of a Grass Blade by Rob Cook

Review of The Day Judge Spencer Learned the Power of Metaphor

Review of The Figure of a Man Being Swallowed by a Fish

Review of Life Cycle Poems by Dena Rash Guzman

Review of Saint X by Kirk Nesset