October 10, 2016

Memoir

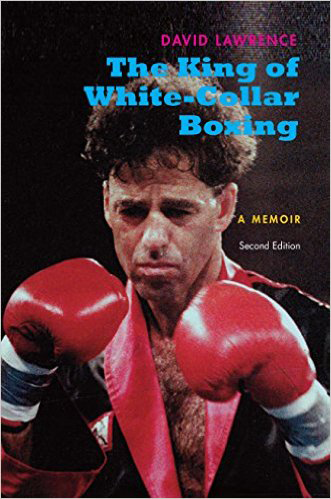

The King of White Collar Boxing

by David Lawrence

Rain Mountain Press, 2016

330 pages

ISBN: 978-0-9968384-8-1

by Brennan Burnside

Reading David Lawrence’s memoir White Collar Boxing, I was reminded of something Mary Karr said about the genre: it isn’t about historical truth or objective facts, but about communicating “the shape of yourself.” Memoirs aren’t journalism. Rather, they are read to learn about, as Karr might say, the attitude of the writer’s soul. What unique filter does the writer have for reality? What is distilled that no other person could’ve quite communicated in the same way? Lawrence’s shape is a narrative at war with itself. Sentences clash in tone and style: an iconoclasm of privilege and destitution. A tension that seems to live deep within Lawrence, created in the subculture of uber-masculinity in a 1980s New York City that would give birth to his side-interests in boxing and rapping (check out his single “The Renegade Jew” on YouTube…not bad) as well as his eventual incarceration for money laundering.

Lawrence emerges from a seething base of rich white males struggling with the ennui and nihilistic tendencies of a maddening matrix of excess and entitlement. An executive in his mid-30s at a prestigious insurance firm in Manhattan, he loses himself in a nostalgia de la boue when he becomes frustrated with the limits that wealth has given to his interior life. A former hippie, he didn’t find the peace that the ‘60s promoted in a myriad of forms. Disillusionment with counterculture idealism evolves into a recalcitrant cynicism: “I am from the love generation that was supposed to save the world. Instead we failed to define it… We assumed that love was simple and that violence was ipso facto negative rather than the first step towards ending violence. We did not know that avoiding the responsibility of war could result in our pacifism killing millions of people in Cambodia and Vietnam… We didn’t understand that violence could be more curative of violence than passivity.” So goes the mission statement behind Lawrence’s long path to becoming a professional boxer in his mid-40s. He leaves the multi-million-dollar skyscrapers of Manhattan for Gleason’s Gym, a small but prestigious gym in Brooklyn with a definite blue-collar vibe (that Lawrence doesn’t hesitate to mention many times over). Gleason’s becomes his self-described “Sorbonne”, where Lawrence cultivates an inner life based on the catharsis of physical abuse.

White Collar Boxing is polemic. It does not dance around definitions: physical violence is holy. For Lawrence, it carries an unadulterated truth: “When I was sixteen I broke my hand against a concrete wall to show how tough I was. I smiled through the pain because I didn’t want to admit how much it hurt. There’s intimacy to suffering.” Fighting becomes a panacea for the culture of deceit and lies he participates in during his working life. While he fails morally in his professional life, prison is not a suitable enough punishment. He must file penance through the sacrifice of his body: i.e., the injuries he suffers in the ring. Boxing, once a hobby to release pent-up aggression, becomes a religion. Something bigger than him. It undoes false, imprisoning concepts of masculinity that entangle him in the financial culture of Wall Street. The survival instincts within the ring cleanse him of the crutches of materialism, humbling him to something greater than wealth. He utters koan-like wisdom in the brash tones of a prize fighter: “To me there was no such thing as contradictions. Opposites merely existed side by side. They didn’t clash.” An utterance born from as experience as much as a desired state of being. He needs to be more than the vanilla caricature of Madison Avenue that he feels that he (and fellow colleagues) have become. The fluid poetry of the boxing ring delivers rough edges and discordant harmony that, ironically, bring him fulfillment.

Likewise, the writing style of White Collar Boxing is an unbalanced, riotous, raucous Kuntlesroman that reads with the vulgar candor of an unschooled hooligan in one moment while embracing the raw beauty of a Bukowskian cadence in the next. It tumbles from the coarse discourse of uneducated youth to striking turns of phrase that encapsulate Lawrence’s education and background in verse (he’s published over 700 poems). There’s a roughness to it that carries the looseness of Outsider Art: a narrative of impulses and late night epiphanies completed by a seeming novitiate. At the same time, a deep insecurity runs through the writing, which Lawrence dodges with cheesy one-liners, speaking in the appropriated brusque of his fellow fighters or the noir discourse of Mickey Spillane. It’s easy to see this as a rookie faux pas, but I don’t accept that this is a mistake. Lawrence’s poetry is far too aware of form to have committed such an error. If he’s anything as a writer, it’s intentional. There is self-knowledge at root in otherwise vacuous braggadocios. A subtle layer of self-satire, an awareness of social position and a deeper concern with how to utilize his privilege properly. Although he may at times appear too self-conscious about his privilege and overtly attempt appropriation of black and Hispanic cultures as a form of supplementing what he feels is an emptiness within his own background, he simultaneously displays respect for those he imitates. The imitation is not without sincerity. There’s a mirthless honesty beneath the shade of appropriate rhetoric and lifestyle. Lawrence, after all, is attempting to live a life of contradictions. To, in his own words, write about “the nature of man.” Most specifically, himself.

Fuel for Love by Jeffrey Cyphers Wright

Alexis Rhone Fancher’s Erotic: New and Selected Poems

Chasing Homer by László Krasznahorkai

Eight Perfect Murders by Peter Swanson

The Death of Sitting Bear by N. Scott Momaday

WHILE YOU WERE GONE BY SYBIL BAKER

MY STUNT DOUBLE BY TRAVIS DENTON

Made by Mary by Laura Catherine Brown

THE RAVENMASTER: My Life with the Ravens at the Tower of London

Children of the New World By Alexander Weinstein

Canons by Consensus by Joseph Csicsila

And Then by Donald Breckenridge

Magic City Gospel by Ashley M. Jones

One with the Tiger by Steven Church

They Were Coming for Him by Berta Vias-Mahou

Verse for the Averse: a Review of Ben Lerner’s The Hatred of Poetry

Ghost/ Landscape by Kristina Marie Darling and John Gallaher

Enchantment Lake by Margi Preus

Diaboliques by Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly

Core of the Sun by Johanna Sinisalo

Maze of Blood by Marly Youmans

Tender the Maker by Christina Hutchkins

Conjuror by Holly Sullivan McClure

Someone's Trying To Find You by Marc Augé

The Four Corners of Palermo by Giuseppe Di Piazza

Now You Have Many Legs to Stand On by Ashley-Elizabeth Best

The Darling by Lorraine M. López

How To Be Drawn by Terrance Hayes

Watershed Days: Adventures (A Little Thorny and Familiar) in the Home Range by Thorpe Moeckel

Demigods on Speedway by Aurelie Sheehan

Wandering Time by Luis Alberto Urrea

Teaching a Man to Unstick His Tail by Ralph Hamilton

Domenica Martinello: The Abject in the Interzones

American Neolithic by Terence Hawkins

Control Bird Alt Delete by Alexandria Peary

Twelve Clocks by Julie Sophia Paegle

Love You To a Pulp by C.S. DeWildt

Even Though I Don’t Miss You by Chelsea Martin

Revising The Storm by Geffrey Davis

Midnight in Siberia by David Greene

Strings Attached by Diane Decillis

Down from the Mountaintop: From Belief to Belonging by Joshua Dolezal

The New Testament by Jericho Brown

You Don't Know Me by James Nolan

Phoning Home: Essays by Jacob M. Appel

Words We Might One Day Say by Holly Karapetkova

The Americans by David Roderick

Put Your Hands In by Chris Hosea

I Think I Am in Friends-Love With You by Yumi Sakugawa

box of blue horses by Lisa Graley

Review of Hilary Plum’s They Dragged Them Through the Streets

The Sleep of Reason by Morri Creech

The Hush before the Animals Attack by Carol Matos

Regina Derieva, In Memoriam by Frederick Smock

Review of The House Began to Pitch by Kelly Whiddon

Hill William by Scott McClanahan

The Bounteous World by Frederick Smock

Review of The Tide King by Jen Michalski

Going Down by Chris Campanioni

Review of Empire in the Shade of a Grass Blade by Rob Cook

Review of The Day Judge Spencer Learned the Power of Metaphor

Review of The Figure of a Man Being Swallowed by a Fish

Review of Life Cycle Poems by Dena Rash Guzman

Review of Saint X by Kirk Nesset