Seen at Théâtre de la Ville, Paris, Fr

(photos courtesy of Toneelgroep Amsterdam)

by Katia Zoritch

June 25, 2015

One fine Thursday evening, I left Théâtre de la Ville and started walking towards Jardin du Luxembourg in order to catch my train home. An hour and 45 minutes of the play’s length into the evening, and everything had already changed in the dark gloss of the lampposts. Often at a moment of even a slight unfamiliarity the mind instantly calls for associations to better situate itself. The places I was passing on my way home after my first time seeing Juliette Binoche act on stage were, conveniently, places from movies where she has starred. I am crossing a bridge across the Seine: here she gloriously waterskied under the burning sky of fireworks on the 14 of July in Leos Carax’s Lovers of the Bridge (a title coincidently reminiscent of one of Van Hove’s latest productions A View from the Bridge). Not far away, somewhere in the 5th arrondissement, Binoche visited a swimming pool in Trois couleurs: Bleu and met a flute player ominously playing her husband’s (or was it her own?) music on the street, on Place Monge. And here, to my right, is Palais de Justice which persistently appears in all three films comprising Kieslowski’s trilogy (perhaps not physically present in Rouge, it has an equivalent in the similar cold hallways of a court in Geneva; it also finds manifestation in the two men Valentine encounters : elderly Trintignant, a former judge, and the neighbor, a young law student who is later featured among the 5 people rescued from shipwreck).

In the context of the play, Palais de Justice serves not only as a convenient reference for the portfolio of “intense roles”, as Binoche herself refers to her professional choices in theatre and film, but a symbol of Ivo Van Hove’s show rising from the urban reality on my way home. Law is the means by which Sophocles’s play operates, moves; it is the gunpowder and the root of the dispute. There is a man who wants to prioritize the law, and across from him — a woman insisting on her own paradoxical interpretation of it. She points out law’s divine origin (“What they call law did not begin today or yesterday — when they say law <..> they mean the unwritten, unfailing, eternal ordinances of the gods that no human being can ever outrun”). At the same time, she runs counter to the infliction of laws from above and claims to know best the principles by which one ought to live in the situation hereby represented. The journal of Théâtre de la Ville quotes Ivo Van Hove who notices that usually “it’s the Chorus that has a very clear idea on what one should and should not do”. It turns out that looking into the history of the past by insisting on the recognition of values and therefore by ‘knowing better’, Antigone battles the history of the present by defying the society around her. One could perceive in her notions of liberal conservatism due to the coexistence of her explosive temper and the solid heritage of morality (this oxymoron had once been attributed to the famous historian Carlo Ginzburg). Emotion and law aim to meet in Antigone just as they enter the space of the stage and the city of Thebes. Back on the pages of the Théâtre Journal, Van Hove confesses: “Much as it is wonderful to stage the duel between Antigone and Creon, it is a fight with no end. The solution lies neither in a society entirely governed by emotion nor in a society entirely controlled by rationale”.

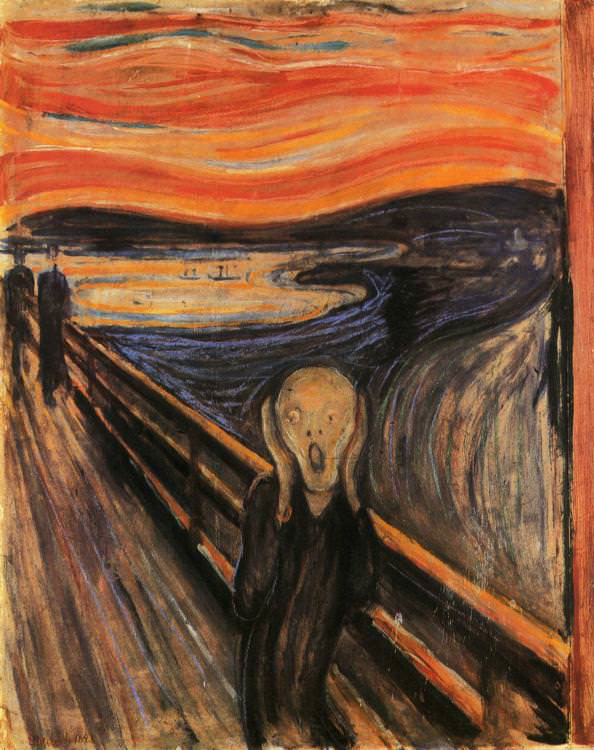

It is the Chorus that intervenes in the duel and serves as a certain intermediary in this juridicial tug-of-war. Like law according to Antigone, Chorus is kind of eternal. After the visit of Tiresias, it utters a menacing line: “I wasn’t born yesterday (“Je n’étais pas née sous la pluie d’hier” runs the French translation on screens above and to the sides of the stage); historically his prophecies are never false”. This notion of adhering to the rules of a different time comes back with Creon’s line at the very end of the play. “I want Creon’s death”, he prays, prostrate on the leather couch. “That’s the future. This is the present”, replies the Chorus on behalf of Ismène who walks by brusquely. “You deal with the present”. To stick up with the ways of one’s own time and the responsibilities it brings along becomes a burden and an invitation to a gaol, literally in the case of Antigone when she is buried alive in a cell underground, and psychologically, when Creon who has been willing to put everyone under his edict and onto his side remains all alone, coiled up in fear, burying his face from the sight of the world that seems to have immediately recovered from the tragedy. Former members of the Chorus, now abstract people, enter the sterile stage and, for the first time in the play, make use of its minimalist interior representing a stylish modern apartment rendered in charcoal tones. Its frontal side, a level below the rising stage where most of the action has taken place reveals a sink, an office table, some shelves, some steps. Several people sit down in a kind of a ditch behind the rising stage. Someone pulls out a typewriter; another person begins to write down at the table, and someone else is sorting small identical-looking objects out nearby. Whatever the action, it is automatic, manually repeated as if on a pipeline, and completely detached, like life itself that chooses to go on no matter what. Its course is taking over with the excellence of a mechanism, bringing its cruel tidal waters onto the tragic site to pronounce the survival of the fittest. In some way, what becomes the ultimate punishment for Creon is an inverted Sartrean verdict, “L’enfer c’est l’absence des autres”, those others being the only people he cared about, and the following estrangement of his fellow citizens. There is no greater loneliness than to be left one on one with the tragic outcome in the very epicenter of the bristling world that couldn’t care less about the ruin of an individual. Creon resembles the creature from Munch’s Scream which may be uttering the sound itself or closing the ears from the scream of the convulsing landscape around. In the distance, two people are walking away; we can only see their calm, indifferent backs. In them rests the promise of a future; without them the painting should have assumed a certain apocalyptic tone. They relate the creature’s situation to the rest of the world; after all, man is the measure of all things. During a reading of Anne Carson’s Antigonick , her superb and innovative translation of Sophocles’s text, at Louisiana Literature Festival in August 2012, a man called Nick, who gives the play its name, is silently walking upon the stage “measuring things”, mostly the characters. My first reaction was to think that he is busy taking their dimensions for future coffins with the repetitiveness of death knocking on the door, but there is no specific requirement for such macabre interpretation. “Here we are, we are fine. We’re standing in the nick of time”, later says Chorus. Once again, Carson emphasizes the grip of the moment. Yet, as a pencil marking of a child’s height remains on the door frame long into the history of the child’s family and the door itself, the nick of Antigone’s sacrifice is evened out by the future of Thebes that gradually becomes its present. Creon is left lying on the stage as a relic of the recent tragedy. Similarly, the figures in Munch’s painting emphasize the creature’s emotion, yet downplay it by moving on, leaving it on the sidewalk. And perhaps the measure added on by abstract Chorus members transforms the tyrannical ruler. In one of the interviews about Antigone , Juliette Binoche says “The play is about humanization of Creon, because he starts on the top of the mountain and has to descend and be a human being”.

While still back at the mountain Creon rivals other entities: one, also known to dwell upon a mountain (Olympus), others — beyond. When he asks Antigone whether she was aware of breaking the law, she responds, “If you call that law. I don’t. Zeus doesn’t. Justice doesn’t. The dead don’t”. So what does the spectator take as the outcome of this confrontation of forces?

There is a passage in Anne Carson’s Antigonick which didn’t make it into her adaptation for the staged version but surely spoke to Ivo Van Hove when he first read it. It follows: “How is a Greek chorus like a lawyer? They are both in the business of searching for a precedent, finding an analogy, locating a prior example. So as to be able to say, this terrible thing we’re witnessing now is not unique, it happened before. We are not at a loss how to think about this, there is a pattern”.

Keeping in mind that Anne Carson translated the text autonomously from Van Hove’s production, this passage almost seems to have come from under his own pen. During a talk with Tony Kushner Van Hove participated at BAM in November 2014 he discusses studying law for three years before turning to stage directing. “In Europe all the laws are no.14, no.42, no.A/B/C, and then you have to make an interpretation of it”, he says, whereas “in America you have to study all the cases. You can prove that you’re right because there was a case in 1934 that was won. I thought it was very interesting and creative, also, to search for that”. To this Tony Kushner replies: “Law is an argument, a dialectic. Theatre is, too”.

This single remark summarizes the correlation of dramaturgic and judicial elements in Van Hove’s production. While Antigone is willing to interpret the omnipresent, divine law, there is Creon willing to establish a precedent. Then, there is Tiresias whose prophecies are credible due to the precedents which had secured their effectiveness. Next is Chorus who, as an intermediary, is willing to both search for a precedent and find the analogy, and ultimately locate a pattern that would shield the people of Thebes from the confrontation of a mistake. All of these characters are involved in an argument against each other, and the dialectic of the play becomes reinforced in its physical manifestation. Actors walk past each other, sit down together, embrace and push. Physical proximity seems to escape no one: the play begins with the two sisters running into each other’s arms across the strong wind. A quote from Plato’s Republic comes to mind here: “We must go wherever the wind of the argument carries us”. (It fits to say that it’s only a natural impulse to evoke quotes here since Carson’s Antigonick also begins with Antigone “quoting Hegel” which “sounds more like Beckett” to Ismène: “We begin in the dark, and birth is the death of us”). Later, when the argument carries Antigone into the palace of Creon for the first time, they talk about the deed she doesn’t deny having committed. Suddenly, Creon sits down on the steps next to her, embraces her and lets her lay her head upon his shoulder, as if the two actors step out of the bodies of their characters and pause in a moment of contemplation just before the action starts to untwist before them. Naturally, soon enough Creon raises his voice; he is later seen violently pushing his son Haemon. Angry and suspicious in the midst of an argument, he comes up to his interlocutors and stares them closely in the eyes, nose to nose, breath to breath.

This novel approach ensuing in physical proximity of characters on stage may serve as a reminder of their relationships beyond it. It is important to keep in mind that the discrepancies of opinions on the burial of Polynices arise from the sinful and incestuous past of Oedipus. A chaos of familial ties has been governing the royal house of Thebes since the marriage of Oedipus and Jocasta, i.e. mother and son. “Whoever we are, think, sister!”, pleads Ismène the first time she sees Antigone. “Father’s daughter, daughter’s brother, sister’s mother, mother’s son — his mother and his wife were one!”. As if due to some genetic malfunction, everyone in the family assumes a double set of roles. Like law in the context of the play, no one is defined in just one axis of norms. Antigone is, at once Oedipus’s daughter and sister, Jocasta’s daughter and granddaughter. Thus Creon, Jocasta’s brother, is simultaneously the sisters’ uncle and their grand-uncle. “Our family is degraded and dirty in every direction”, proclaims Ismène who herself is simultaneously Antigone’s sister and a member of Chorus in Van Hove’s production, just as Tiresias and Eurydice who also occupy a double set of roles. And yet certain familial connections may be assigned a different value, more substantial and authentic than others. “A husband or a child can be replaced, but who can grow me a new brother?”, laments Antigone. Siblings seem to Antigone to be a part of her own, equal to her self. Curiously, Ismène’s denial to help her sister in burying their brother is fortuitously reflected in the pronunciation of her name in Russian, which literally translates to “betrayal” — while in Ancient Greek it is derived from the word “knowledge”. Ismène refuses joining Antigone by reminding her that “girls cannot force their way against men”. By protesting against Creon’s edict Antigone once again points out role misplacement in the society of Thebes; by protesting against the rule of one man, she protests against all of them. Isméne is, perhaps, not wrong and even ‘knowledgeable’ in warning Antigone (remember Hegel who called “womankind the everlasting irony in the life of a community” in Phenomenology of Spirit ). However, Creon is not simply a man and the head of Thebes; he thinks to be its sole owner. It is Haemon who later argues with him: “No single human being has perfect knowledge! No city belongs to a single man”. Creon’s own error tops the chain of previous misfortunes, and confirms the pattern of fatal aberration. After a long and stubborn denial, Creon is finally awoken by the words of Tiresias: “You’ve made a structural mistake with life and death, my dear! You’ve put the living underground and kept the dead up here”. Tiresias issues an ominous pause, similar to the one later issued by Eurydice, Creon’s wife, but unlike her, shakes his blind head and adds: “That is so wrong. That is so wrong”. These are, perhaps, the most chilling words in the play. They establish a certain inverted reflection of the play’s first lines, when Ismène asks Antigone who hasn’t yet got a chance to share her plan, “What is the matter? You have your thunder look”. Words of Tiresias are instead pronounced by a blind prophet, and they assume a tone of utter despair only through his voice, with no accentuation by the way of his expression or look. If Ismène’s question comes in a general anticipation of the news, the words of Tiresias come too late, and serve not as a piece of advice or a warning, but as a verdict and a lament for the piling “archives of grief falling upon the house”. Addressed to the ruler of Ancient Thebes, they ricochet towards us: archives of grief may as well be our own archives, of history not yet as ancient as the Ancient Greek.

In fact, perhaps that’s why the play features no marker of Ancient Greece. Creon is bald and is seen sporting an elegant suit; seen from afar, his wife reminded me of Charlotte Rampling in a long camel trench coat. Ismène is clattering around the stage in stilettos, arms crossed. The aforementioned apartment is very geometric, and the entrance to the king’s rooms is a simple rectangle with a circle of changing light above it. Visuals of slow-motion street views are projected onto the wall; one can make out other men is suits, an elderly woman, a middle-aged passer-by. Another modern reference that fits very neatly into Van Hove’s portrayal of Thebes is a closing song, Velvet Underground’s “Heroin”. As Creon lies down onto the leather couch in a gesture at once reminiscent of psychoanalysis and almost childish despair, we begin hearing the familiar guitar chords. Yet what is most surprising is the aptness of the lyrics, as if they were coming out of Creon’s mouth proper. The song begins with Creon’s incentive at the start of his rule: “I don’t know just where I’m going/ But I’m gonna try for the kingdom, if I can”. 7 lines into the song, it assumes a grimmer tone: “I have made big decision/ I’m gonna try to nullify my life”. The tone further aggravates as if Lou Reed was describing the ill-fated city of Thebes itself: “Away from the big city / Where a man cannot be free/ Of all the evils of this town/ And of himself and those around”. Finally, Reed chants lines that seem to be addressed directly to Creon wailing on the couch: “And all the politicians making crazy sounds/ And everybody putting everybody else down/ And all the dead bodies piled up in mounds”. In not letting Antigone bury her brother, Creon himself triggers the piling of bodies, and buries his entire family. The irony of fate sees to it that Creon remains all alone while Antigone is in a ‘mound’ with others. Before it was her alone opposed to a society governed by his customs, and it seems as if she preferred it that way, too. “Leave my death alone”, Antigone tells Ismène when the latter attempts to share her responsibility over the committed crime in front of Creon. Antigone’s name reveals a phonic semblance to her nature, for she starts out as antagonistic to such society. And yet it’s Creon who ends up bearing the torch. He arrives at a point of reconciliation with Antigone by understanding her concept of pain. Earlier in the play she gives a simple definition of it: “Of course I will die, Creon or no Creon, and death is fine. Death has no pain. To leave my mother’s son lying out there — that would be pain”. The wisdom of these words depends on no edict; they sound as wise to our ears as they should to Creon’s. In some way their timelessness would be described by Kierkegaard’s phrase “The tyrant dies and his rule is over, the martyr dies and his rule begins”, and only having lost this source of wisdom in the martyr does Creon understand it. He is now “perfectly blended with pain”, perhaps like Oedipus himself to whom the wisdom reveals his mistakes and further committed atrocities. In Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being , later adapted for a movie with Juliette Binoche (sic!), Tomáš wished a similar fate for the old Czech communists who’d witnessed the failure of their beliefs and subsequently came face to face with the crimes committed along the way. At the end of Van Hove’s play we are not yet aware of Creon’s next step; only Lou Reed’s melodic voice calls for the pain’s annihilation — “Heroin, be the death of me” — and in Anne Carson’s text Nick ‘continues measuring’.

Photos courtesy of Toneelgroep Amsterdam

Transcending Passages, Maisoon Al Saleh, March 16th - April 6th, 2021

Unbound Perspectives - SEPTEMBER 26-OCTOBER 17, 2020

East Villager Billy The Artist Climbs Atop Ai Wei Wei's Fence To Shine A Light On It

A Quick Note on Transplants: Greek Diaspora Artists

Teddy Thompson’s Ultimate Funeral Mix Tape

Moray Hillary, Pre-New Reflective by Heather Zises

SELFISH, Review by Heather Zises

Winter Realm Series by Noah Becker

Paul Rousso at Lanoue Fine Art

Airan Kang, The Luminous Poem at Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery

Damien Hoar De Galvan at Carroll and Sons

Accumulation: Sculptural work by Alben at Gallery Nines

Karen Jerzyk's unsettling Parallel World

CEK - Concrete Functional Sculptures

Alexis Dahan, ALARM! At Two Rams

Do Ho Suh, Drawings, at Lehmann Maupin

Nir Hod, Once Everything Was Much Better Even the Future

Exhibition Review: Mario Schifano 1960 – 67

Subverting the Realist Impulse in the Work of Shauna Born

Linder: Femme/Objet by Erik Martiny

What We Do in the Shadows by Jemaine Clement and Taika Waititi

Justin Kimball at Carroll and Sons

Told & Foretold: The Cup in the Art of Samuel Bak, at Pucker Gallery

Collective Memory Manipulated: Sara Cwynar’s Flat Death

Art Paris Art Fair 2013 Review

Paris Street Art Musée de la Poste

Trellises by Katherine Tzu-Lan Mann

Topography of Destruction Kemper Museum

L'art en Guerre : France 1938-1947

The Louvre Relocates to Africa

A French Priest, Tears and Fire the Art of Jean-Michel Othoniel