by Raqi Syed

April 02, 2015

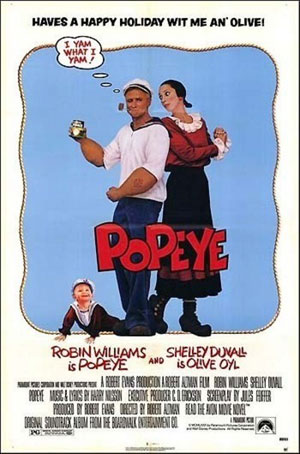

The first thing I learned in film school was this: when introducing yourself in class, name your road to Damascus; the film that started it all for you. Acceptable answers are Star Wars, Jaws, Breathless, Persona. Any Truffaut film would do, and the second [or fifth] Star Wars was preferable. An unacceptable answer I quickly learned, would be Popeye. Never mind that it played for years at our local Milwaukee drive-in, or that later in California, I saw it every time it was broadcast on KTLA’s Family Film Festival. Popeye I learned, was an embarrassment to all concerned—those who made it and those who enjoyed watching it. For the price of making the film, Robert Altman spent a decade in the wilderness of European cinema. In film school I stopped answering the question about what kind of movie set my childhood soul on fire. I became immersed in the language of cinema, and stopped thinking about Popeye.

The first thing I learned in film school was this: when introducing yourself in class, name your road to Damascus; the film that started it all for you. Acceptable answers are Star Wars, Jaws, Breathless, Persona. Any Truffaut film would do, and the second [or fifth] Star Wars was preferable. An unacceptable answer I quickly learned, would be Popeye. Never mind that it played for years at our local Milwaukee drive-in, or that later in California, I saw it every time it was broadcast on KTLA’s Family Film Festival. Popeye I learned, was an embarrassment to all concerned—those who made it and those who enjoyed watching it. For the price of making the film, Robert Altman spent a decade in the wilderness of European cinema. In film school I stopped answering the question about what kind of movie set my childhood soul on fire. I became immersed in the language of cinema, and stopped thinking about Popeye.

Recently, as I witness the steady stream of live action comic book movies hitting theaters one after another—what we now call franchises—it has come back to me. For isn’t Popeye the prototype, the ur-summer-tentpole we are now so familiar with? Both Jaws and Star Wars may have been blockbusters, but not in the calculated way that Popeye and its offspring would come to be. (It is useful to note that Popeye was conceived as a response to the studio’s failure to secure rights to the musical Annie. The early Ants to A Bug’s Life.) What is most interesting about Popeye is the anachronistic relationship between its directorial vision and its studio driven pedigree.

Without Popeye there would be no Batman, no Dick Tracy. Popeye is the genesis of Hollywood’s obsession with Marvel and DC. But the evolution has been one of aesthetic riches and emotional impoverishment. Where Popeye was earnest, handcrafted, charmingly awkward, its successors choose to be ironic, slick, and violent. Shelley Duval as Olive Oyl most of all remains the symbol of a time long past. In which women could embody all kinds of qualities that did not revolve around them being neutered stand-ins for Peter Pans who wish only to run around in tights, wielding phallic objects. The heroic antics of Popeye revolved strictly around the orbit of a family melodrama. His estranged father, his lover, and his adopted son motivate the action. He doesn’t want to fight. He remains indifferent to his super powers until the last ten minutes of the film. The contemporary comic film has abandoned the family for sexual repression and latently homosocial fight scenes. Family melodrama in turn, has been relegated to the lower rung of feature cartoons.

The idea that an indie arthouse filmmaker would have set the standard for a kind of filmmaking that is now strictly the milieu of mainstream blockbusters is intriguing. As if Paul Thomas Anderson were to direct the next Marvel film. But the very idea that Robert Altman would make a movie like Popeye can only be understood as further evidence of his avant-garde sensibility. He was more interested in the ensemble nature of the storytelling. Popeye himself exists in a universe with many characters vying for control of the action. We get as always, the signature Altman overlapping dialogue, zooming camera, and episodic narrativity. The singular hero is moderated by an emphasis on the community of Sweethaven. The best way to understand Popeye may be in the context of a transitionary moment in Hollywood. First blood had already been drawn three years earlier with Star Wars, but films like Heaven’s Gate proved to be emblematic of the kind of artsy moviemaking that could bring a studio to financial ruin. Popeye sat right at the center of this increasing attraction to mythical heroes and aversion to risk. And so it still remains a one of a kind film: a quirky arthouse Altman experiment given blockbuster treatment. It does make me wonder what would happen if the Paul Thomas Andersons were given opportunities to make all kinds of films. It is possible it would not be a financially sound decision. But it is also possible the result would be films that endure rather than shoot off a giant box office wad of buzz and disappear from our minds forever.

From Russia, With Love A review of SCREENS: A Project About “Community”

Basquiat—The Unanswerable Answer to the Art World

Let’s talk about the hard stuff: Get Out

May It Last: A Portrait of the Avett Brothers

Move Over Hogwarts—The Practical Magic Is at Headfort

The Dog Days of Summer—Two Ways to Beat the Heat

The Mistress, the Publisher, His Son & His Mother

Santoalla-- the Spaces Between

Reading Arthur Miller in Tehran, The Salesman

Killing the ISIS Propaganda Machine, City of Ghosts

Bewitched, Bothered and Beguiled, The Beguiled– A Film Review

A Spoonful of Sugar-- Not Saccharine The Big Sick: A Film Review

Fiona and the Tramp, Lost in Paris- a review

Movie Review: Beatriz at Dinner

Cameraperson, dir. Kristen Johnson: stories from behind the camera lens

SELFISH, Review by Heather Zises

Winter on Fire: Ukraine’s Fight For Freedom, dir. Evgeniy Afineevsky

Strange Days directed by Kathryn Bigelow (1995)

World of Tomorrow and the Quit-Bang Language of the Future

Quintet, Directed by Robert Altman, 1979

Classic Movie Short Review: Croupier (1998)