by Raqi Syed

August 06, 2015

Young men routinely pulled over by the police for driving while black. Racially conscious rap artists lauded by ordinary citizens as cultural bards, and decried by local city governments as fomenters of hate. A politically charged and increasingly connected social media landscape in which citizens take to the streets armed with technology, proving through video surveillance what internal affairs investigations in police departments all over the country have been denying for years. An entertainment industry capitalizing on titillating first person video captured by young people in conflict zones. And a Federal government struggling to address the issue of an increasingly militarized police force waging war on the citizens of its cities.

Young men routinely pulled over by the police for driving while black. Racially conscious rap artists lauded by ordinary citizens as cultural bards, and decried by local city governments as fomenters of hate. A politically charged and increasingly connected social media landscape in which citizens take to the streets armed with technology, proving through video surveillance what internal affairs investigations in police departments all over the country have been denying for years. An entertainment industry capitalizing on titillating first person video captured by young people in conflict zones. And a Federal government struggling to address the issue of an increasingly militarized police force waging war on the citizens of its cities.

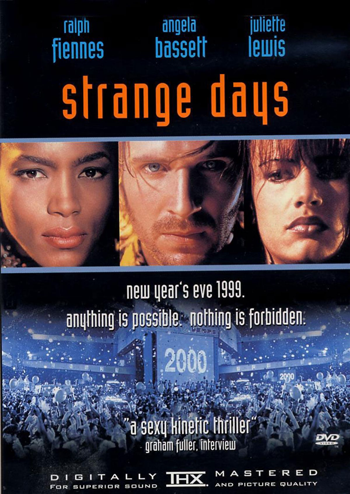

I’m not talking about Ferguson, or Staten Island, or Beavercreek Ohio. I’m not even talking about the year 2015. But rather, the fictional millennium of Los Angeles as imagined twenty years ago in Kathryn Bigelow’s near future sci-fi virtual reality film, Strange Days. In which Ralph Feinnes plays a sleazy (but charming) ex-cop turned black market VR dealer. The VR market is based around an illegal device called SQUID (Superconducting Quantum Interference Device), allowing a user to record input directly from their cerebral cortex. This memory can then be played back and experienced via all senses by the viewer. It’s no surprise that snuff VR is the most coveted (and illegal) kind of experience to be had. Feinnes here is equal parts Roger Corman and Daryl Gates. Played out in the heyday of the Fox TV docudrama, Cops, Feinnes’s Lenny Nero sits at the intersection of real police work and its value as entertainment.

I saw Strange Days in 1995 when it played in theaters—the experience brought down somewhat by the simultaneous release of another neo noir VR film — Johnny Mnemonic. Chalk it up to one of Hollywood’s many Bug’s Life versus Ants moments. Variations in budget, effects work, and quality of storytelling, gave us a whole spectrum of VR movies in the 1990’s. But the development of actual VR technology and the incredible buzz surrounding it, accomplished little more at that time than a few blockbuster movies delivering passive cinema, and the promise of a new immersive media experience that had already fizzled by the time Y2K threatened the end of the networked world. With the release of the third Matrix film in 2003, we really had moved on, and our interest in VR was just one more aspect of the 20th century that felt dated. VR was the jetpack of the 90s—it promised much but delivered little.

But now, it feels like we’re gonna party like it’s 1995 again, and it’s easier to ask in 2015, who isn’t talking about VR? The hype has prompted me to reconsider what we thought the technology would be the last time around, against our expectations of it now.

Strange Days positions VR as a tool for documenting, even instigating, social change. The film offers us a vision of what it would be like if VR went to the streets. What we have now is a kind of segregating of VR. Big tech money combined with drabs of Hollywood money, coming together with the promise of beautiful immersive storytelling. There’s a lot of talk about world building, improved pixel density, compatible platforms, and the auteurs who want to jump in and cinematically redefine the tech. Where we seem to be headed is towards Birdman—an art directed passive experience sold to us under the guise of a first person genre defying spectacle. Meanwhile, the dirty work of documenting the political landscape as it really exists, remains squarely in the hands of indie documentary, police body cams, and young people armed with mobile phones and Facebook accounts. There is little crossover here. Nor much big money being directed at the next level SQUID device that is going to bring the experience of the protestor into the cerebral cortex of suburban moviegoers.

Perhaps the flaw in the past discourse surrounding VR was a matter of expectation. Strange Days shows us that powerful technology wielded by those with vision can lead directly to addressing social injustice. A revolution not against aliens or mysterious evil forces, but against our worst selves. Some may argue social media has in fact played a hand in the revolutionary movements of the 21st century. And there are others who would point to the internet as television reloaded—yet another passive platform of consumption. Which category VR tech falls into could yet be determined. So far however, VR itself has done little more than allow us to play video games in bigger arenas, and wage war in a more clinical manner. It is certainly not the revolution we hoped for.

From Russia, With Love A review of SCREENS: A Project About “Community”

The Inner Strength of Joan Didion

Basquiat—The Unanswerable Answer to the Art World

Let’s talk about the hard stuff: Get Out

May It Last: A Portrait of the Avett Brothers

Move Over Hogwarts—The Practical Magic Is at Headfort

The Dog Days of Summer—Two Ways to Beat the Heat

The Mistress, the Publisher, His Son & His Mother

Santoalla-- the Spaces Between

Reading Arthur Miller in Tehran, The Salesman

Killing the ISIS Propaganda Machine, City of Ghosts

Bewitched, Bothered and Beguiled, The Beguiled– A Film Review

A Spoonful of Sugar-- Not Saccharine The Big Sick: A Film Review

Fiona and the Tramp, Lost in Paris- a review

Movie Review: Beatriz at Dinner

Cameraperson, dir. Kristen Johnson: stories from behind the camera lens

SELFISH, Review by Heather Zises

Winter on Fire: Ukraine’s Fight For Freedom, dir. Evgeniy Afineevsky

3 Women, Directed by Robert Altman, 1977

World of Tomorrow and the Quit-Bang Language of the Future

Quintet, Directed by Robert Altman, 1979

Classic Movie Short Review: Croupier (1998)