Poetry

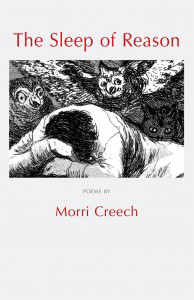

The Sleep of Reason

by Morri Creech

The Waywiser Press

72 pages

ISBN: 978-1904130536

by Noel Sloboda

About Noel Sloboda

Noel Sloboda is the author of the poetry collections Shell Games (sunnyoutside, 2008) and Our Rarer Monsters (sunnyoutside, 2008), as well as several chapbooks, most recently Circle Straight Back (Červená Barva Press, 2012). Sloboda has also published a book about Edith Wharton and Gertrude Stein. He teaches at Penn State York.

The Sleep of Reason is like a fantastic milkshake: Greedy readers who try to consume it quickly will end up with a headache, but those who pace themselves are in for a treat. The book, Creech’s third, is lent flavor and density by his exquisite craftsmanship. Although the thirty-one poems included here take a wide range of forms—ranging from three lines to eight pages; from sonnets to prose poems—all of them are musical, robust, and balanced, even as they treat complex ideas. It is the sophisticated and sometimes somber ways in which these ideas are handled that will lead to brain freeze in overeager readers. Creech’s poems do not function as mere entertainment; they are learned and intricate, both in form and in content, addressing subjects such as time, faith, and nature. Creech’s poetry is meant to linger: to keep audiences up late thinking about the care that went into their construction and their philosophical implications.

As the Goya-inspired title suggests, Creech values the visual arts, and several of the poems in The Sleep of Reason are dedicated to paintings (“Goldfinch”) or photographs (“Night Blooming Cereus”). One such ekphrastic, the triptych “The Perils of Art,” serves as a sort of ars poetica. It centers on the idealistic sensibilities of the speaker’s nine-year-old niece, who is as yet uninitiated in the appeal of the sublime.

So what do I tell my niece—

that things conceived in terror

eclipse some works of peace?

that vision redeems the error?

How the grotesque compels the imagination—of a painter, photographer, or poet—is of abiding interest for Creech, who frequently seizes upon what disturbs him. He targets the greed of the business world in “On Corporate Money as Political Speech” and complains of the unnatural pressures of “Banking Hours.” More frequently, though, he offers subtly unsettling scenes from everyday life, dwelling on embers that mask a drowsy child’s face beside a “Night Fire” or the eerie silence before a “Dirge at Evening.” Yet, always for Creech such moments can be constructively framed, if not perhaps redeemed, by forms from the past.

Creech delves deeply into how classical precedents might impose meaning on a “bedlam universe” in two long poems about John Keats: “Song and Complaint” and “Cold Pastoral.” In the former, the speaker begins by rebuking the famous nightingale: “Beat it, bird. We’ve heard enough.” However, once the bird is gone, the speaker acutely feels the absence, deciding to “pace / and listen awhile. As long as I have time.” The alternative—nothingness—is less appealing. In the other Keats poem, as the nightingale is given voice, the consequences of not investing in something are once again explored, this time in relation to the imminent death of the tubercular British poet. Creech evokes the anxiety of enduring such a condition, but he asserts the joy of life even while acknowledging the difficulty of believing it matters. At the close of the poem, the nightingale bears witness as Keats’s existence “cramps into a room for one,” and rather than fade away, it forever “unfolds inside your [Keats’s] mind”—and, of course, in song.

Although a major figure in The Sleep of Reason, Keats is hardly the only literary luminary to appear in its pages. Creech speaks of Thomas Hardy and Dante Alighieri, while alluding to Robert Frost, T.S. Eliot, Wallace Stevens, and William Shakespeare. (Surely too part of why Creech is drawn to Keats is this forebear’s love of older writers such as Homer.) Creech also takes many cues from the canon in shaping his poems, firing them in traditional molds even when speaking about iPods, Humvees, and “flat screen[s] rich with bric-a-brac.” The rhymes and metrics never come at the expense of the vernacular; Creech’s artistry is all the more powerful for being understated. That said, he does address the challenge of bringing elegant (and for some readers archaic) forms to bear on twenty-first century experiences. In “Trouble,” the speaker observes a property overrun by blackbirds, stating that the owner has apparently tired of driving them away after having “had enough of order.” At odds with this pronouncement, however, are neat quatrains and a consistent rhyme scheme. Similar tensions manifest in other poems, as terrorist attacks and stock market crashes engender doubt, fatigue, and skepticism. But invariably these feelings are contained in measured lines and stanzas; made manageable (and meaningful) when cast in relation to history. The speaker of “Lullaby: Under the Sun” concludes that even though he rationally anticipates hearing about “some Passchendaele or Austerlitz / that has or hasn’t happened yet,” he is content for a few moments to watch his sleeping daughter: “Made on such stuff / the lovely world seems true enough.”

In “Landfill,” Creech assays the familiar trope of the garbage dump, tackled memorably before by Stevens and A.R. Ammons. Creech is less playful than these earlier writers as he investigates “What brings / us back here?” but he is no less committed to getting to the bottom of the question. While Creech mucks about in “a strew of rinds and punctured bags,” he hopes to make something serviceable out of it. He does not revel in imagination or wit. Instead, he discovers empathy for others when studying discarded artifacts:

Someone wore those wing-tipped shoes,

dozed on that mattress, the Daily News

bundled and stacked there; surely there were faces

that stared from these empty frames.

A comparable impulse carries through a focused reflection on wartime memorabilia: “Heirloom: Nazi S.S. Cigarette Lighter.” The implement awakens not just a sense of foreboding in the speaker but also an awareness of the bond he shares with those who suffered in the flames of World War II. The lighter generates a literal and figurative “spark” that broadens his perspective, engendering a momentary sense of transcendence: “Then I see it all— / my face in the window, shadow on the wall.”

Not everybody likes milkshakes, of course, and The Sleep of Reason will be too cerebral for some readers. Creech works in a university, and it shows. His poems chronicle intellectual problems, not emotional crises. Nor does he provide personal revelations, like many post-confessional writers, to solicit sympathy and interest. With that stated, Creech is passionate about the ideas he explores. And he always grounds his concepts in the particular. When “history [...] shrinks to a lidless socket” in The Sleep of Reason, it is within “The Stone Well at Mt. Pisgah Church.” The book is replete with comparably textured meditations, many of them profound, each presented with a challenge. Creech pushes readers to confront history while encouraging them to find features in it that enlarge their present; to wake from the sleep of reason without forgetting the inspirational power of last night’s dreams.

Alexis Rhone Fancher’s Erotic: New and Selected Poems

Chasing Homer by László Krasznahorkai

Eight Perfect Murders by Peter Swanson

The Death of Sitting Bear by N. Scott Momaday

WHILE YOU WERE GONE BY SYBIL BAKER

MY STUNT DOUBLE BY TRAVIS DENTON

Made by Mary by Laura Catherine Brown

THE RAVENMASTER: My Life with the Ravens at the Tower of London

Children of the New World By Alexander Weinstein

Canons by Consensus by Joseph Csicsila

And Then by Donald Breckenridge

Magic City Gospel by Ashley M. Jones

One with the Tiger by Steven Church

The King of White Collar Boxing by David Lawrence

They Were Coming for Him by Berta Vias-Mahou

Verse for the Averse: a Review of Ben Lerner’s The Hatred of Poetry

Ghost/ Landscape by Kristina Marie Darling and John Gallaher

Enchantment Lake by Margi Preus

Diaboliques by Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly

Core of the Sun by Johanna Sinisalo

Tender the Maker by Christina Hutchkins

Conjuror by Holly Sullivan McClure

Someone's Trying To Find You by Marc Augé

The Four Corners of Palermo by Giuseppe Di Piazza

Now You Have Many Legs to Stand On by Ashley-Elizabeth Best

The Darling by Lorraine M. López

How To Be Drawn by Terrance Hayes

Watershed Days: Adventures (A Little Thorny and Familiar) in the Home Range by Thorpe Moeckel

Demigods on Speedway by Aurelie Sheehan

Wandering Time by Luis Alberto Urrea

Teaching a Man to Unstick His Tail by Ralph Hamilton

Domenica Martinello: The Abject in the Interzones

Control Bird Alt Delete by Alexandria Peary

Twelve Clocks by Julie Sophia Paegle

Love You To a Pulp by C.S. DeWildt

Even Though I Don’t Miss You by Chelsea Martin

Revising The Storm by Geffrey Davis

Nature's Confession by J.L. Morin

Midnight in Siberia by David Greene

Strings Attached by Diane Decillis

Down from the Mountaintop: From Belief to Belonging by Joshua Dolezal

The New Testament by Jericho Brown

You Don't Know Me by James Nolan

Phoning Home: Essays by Jacob M. Appel

Words We Might One Day Say by Holly Karapetkova

The Americans by David Roderick

Put Your Hands In by Chris Hosea

I Think I Am in Friends-Love With You by Yumi Sakugawa

Box of Blue Horses by Lisa Graley

Review of Hilary Plum’s They Dragged Them Through the Streets

American Neolithic by Terence Hawkins

The Hush before the Animals Attack by Carol Matos

Regina Derieva, In Memoriam by Frederick Smock

Review of The House Began to Pitch by Kelly Whiddon

Hill William by Scott McClanahan

The Bounteous World by Frederick Smock

Review of The Tide King by Jen Michalski

Going Down by Chris Campanioni

Review of Empire in the Shade of a Grass Blade by Rob Cook

Review of The Day Judge Spencer Learned the Power of Metaphor

Review of The Figure of a Man Being Swallowed by a Fish

Review of Life Cycle Poems by Dena Rash Guzman

Review of Saint X by Kirk Nesset