March 25, 2016

Poetry

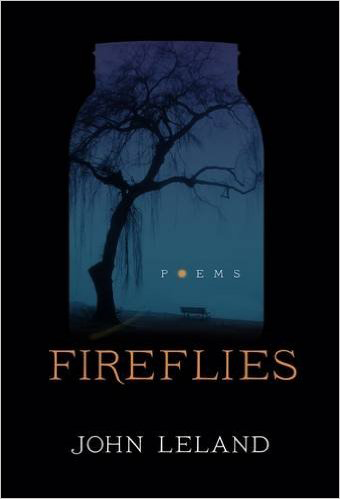

Fireflies

by John Leland

Mercer University Press, 2015

56 pages

ISBN 978-0-88146-550-1

by Brennan Burnside

About Brennan Burnside

Brennan Burnside’s work most recently appears in Word Riot, Maudlin House and Loud Zoo. His chapbook, Room Studies, is available from Dink Press.

When I read John Leland’s Fireflies, I felt the guttural tug of Samuel Coleridge’s definition of elegy: that “the poet…presents everything as lost and gone or absent and future.” In Leland’s poems, the “lost and gone,” and “the absent and future” are speakers lavishing and languishing in the irresolution of the present moment.

Leland captures long panoramic journeys, lives and generations in short metered verses. His characters dip their heads toward the future and drown in the present. In “On Song,” Leland follows a bullfrog’s long trek toward a distant, unnamed (and perhaps nonexistent) destination: “Grown old jug-jugarumping/ to a bog indifferent to your song/ you chant half-heartedly your requiem/ out more of habit than of hope, and quit,/ resigned tonight to personal extinction.” The poem is one of many that express the loneliness and futility of the future, the restlessness of the present and the necessity of hope for hope’s sake.

Despite the sardonic tone Leland takes toward more imaginative gestures (i.e. “hope”), he never dismisses them. In “Casting,” a character tries to reconcile an idyllic memory of his father fishing with the reality of what might’ve been beneath that moment so long ago: “red in the vague tug of twined thread/ the terrors of the trapped/ then draw them, slowly/ towards the sunlight and death.” The poem encapsulates a binary Leland will bring forth again and again, that of realization versus imagination. The poem asks if viewing the world cynically (a particular form of “the real”) is of any greater worth than the notion that life is an imaginative landscape.

Leland doesn’t seem to take one side or the other. His poems simultaneously praise the joy of imaginative perception but also languish in the bitter “reality” of the sullen emotions underlying them. In “Cocktails,” he notes “how disappointed one is/ when middle age’s lowering clouds/ close in on one’s horizons, how preferable to strike at those around one rather than oneself.” The issue is not whether the world is fundamentally materialist or not. Rather, our responsibility, according to Leland, is to be a self-actualizing agent in the present moment. In other words: compromise.

Coleridge’s definition of elegy as either conveying the “lost and gone” or “absent and future” is something Leland plays with by putting the two ideas in conversation with the equally troublesome binaries of imagination and realization. In “Fireflies,” Leland describes the child-like capturing of fireflies with the gruesome discovery of a “jam jar filled with light/ grasped tight in fingers green with gore” and soberly relates “How you rose the morrow morn/ to a jam jar dark and dead/ and overheard your life’s lid turn/and caught your breath on air gone stale?” We create sorrow for ourselves and others in our search for beauty and in our desire for order. But this, Leland’s verse implies, is the price of trying to straddle the binary of real and imaginary worlds.

In “Conjugating Verbs” Leland notes how the self is stretched between the imaginary and the real “like the deceptions we all play upon/ ourselves, remembering as in a film/ ourselves outside ourselves, driving a car/ or eating lunch, or this: kissing, eyes closed.” We imagine ourselves as part of a landscape trapped within our imagination. But time disrupts our tender fancies. We protest, but, Leland notes, we also willingly participate and make compromises in order to enjoy our fantasies. We live an unreconciled life but are amused by its awkwardness. We welcome life’s mysteries, destructiveness and eventually, its interruptions.

Alexis Rhone Fancher’s Erotic: New and Selected Poems

Chasing Homer by László Krasznahorkai

Eight Perfect Murders by Peter Swanson

The Death of Sitting Bear by N. Scott Momaday

WHILE YOU WERE GONE BY SYBIL BAKER

MY STUNT DOUBLE BY TRAVIS DENTON

Made by Mary by Laura Catherine Brown

THE RAVENMASTER: My Life with the Ravens at the Tower of London

Children of the New World By Alexander Weinstein

Canons by Consensus by Joseph Csicsila

And Then by Donald Breckenridge

Magic City Gospel by Ashley M. Jones

One with the Tiger by Steven Church

The King of White Collar Boxing by David Lawrence

They Were Coming for Him by Berta Vias-Mahou

Verse for the Averse: a Review of Ben Lerner’s The Hatred of Poetry

Ghost/ Landscape by Kristina Marie Darling and John Gallaher

Enchantment Lake by Margi Preus

Diaboliques by Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly

Core of the Sun by Johanna Sinisalo

Maze of Blood by Marly Youmans

Tender the Maker by Christina Hutchkins

Conjuror by Holly Sullivan McClure

Someone's Trying To Find You by Marc Augé

The Four Corners of Palermo by Giuseppe Di Piazza

Now You Have Many Legs to Stand On by Ashley-Elizabeth Best

The Darling by Lorraine M. López

How To Be Drawn by Terrance Hayes

Watershed Days: Adventures (A Little Thorny and Familiar) in the Home Range by Thorpe Moeckel

Demigods on Speedway by Aurelie Sheehan

American Neolithic by Terence Hawkins

Wandering Time by Luis Alberto Urrea

Teaching a Man to Unstick His Tail by Ralph Hamilton

Domenica Martinello: The Abject in the Interzones

Control Bird Alt Delete by Alexandria Peary

Twelve Clocks by Julie Sophia Paegle

Love You To a Pulp by C.S. DeWildt

Even Though I Don’t Miss You by Chelsea Martin

Revising The Storm by Geffrey Davis

Midnight in Siberia by David Greene

Strings Attached by Diane Decillis

Down from the Mountaintop: From Belief to Belonging by Joshua Dolezal

The New Testament by Jericho Brown

You Don't Know Me by James Nolan

Phoning Home: Essays by Jacob M. Appel

Words We Might One Day Say by Holly Karapetkova

The Americans by David Roderick

Put Your Hands In by Chris Hosea

I Think I Am in Friends-Love With You by Yumi Sakugawa

box of blue horses by Lisa Graley

Review of Hilary Plum’s They Dragged Them Through the Streets

The Sleep of Reason by Morri Creech

The Hush before the Animals Attack by Carol Matos

Regina Derieva, In Memoriam by Frederick Smock

Review of The House Began to Pitch by Kelly Whiddon

Hill William by Scott McClanahan

The Bounteous World by Frederick Smock

Review of The Tide King by Jen Michalski

Going Down by Chris Campanioni

Review of Empire in the Shade of a Grass Blade by Rob Cook

Review of The Day Judge Spencer Learned the Power of Metaphor

Review of The Figure of a Man Being Swallowed by a Fish

Review of Life Cycle Poems by Dena Rash Guzman

Review of Saint X by Kirk Nesset