Fiction

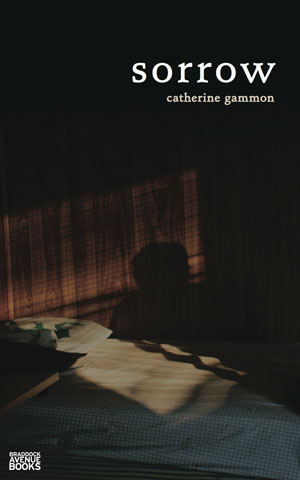

Sorrow

by Catherine Gammon

Braddock Avenue Books

2013

304 pages

ISBN: 978-0-615-80861-1

Review by Mike Hampton

Catherine Gammon’s second novel Sorrow is a dense exploration of the interior lives of characters who exist on the brink. Readers are invited to enter the shattered life of Anita Palatino and connect the shards of her past, her present, and ultimately, her mind. They are asked to consider what choices they would make if they were immigrant refugees from a civil war who suddenly had to speak with the police. They are charged to walk with a nun who doubts her ability to help and considers her faith a consequence of chance. They are left to explore whether passion is an escape from despair or solely a trap sprung when hurting gets too much to bear.

The novel’s protagonist Anita is buried under the shame of her nightly excursions, the pain of sexual abuse, anger, and her inability to be only one person. In the night she is often overtaken by base urges which transform her into an allegory for lust, rage, and fear. The results of her actions during these periods leave her to hide or reconcile what she’s done when she was a different shade of herself.

While Anita’s actions set the narrative in motion, those who inhabit her world are just as richly rendered and conflicted and each has a secret singular mourning. Anita’s mother has a lifeless existence and is a prisoner in her apartment which she remains. Cruz Garcia and his cousin Tomas bear the wounds of the El Salvadorian civil war as they try to care for Anita and avoid the unwanted attention and grief she brings. Her poor community of refugees and lost souls feels at once threatened by her and desperate to come to her aid as best they can, if only because she represents their lives in a sense: locked by the past, surviving, and praying for deliverance. Sister Monica speaks of this communion even when Anita’s guilt grows clearer, “We seemed so alike in those days…Alone in our hearts, secrets, and hungry for meaning, for mystery—some more truthful way of life, an otherworldly but still human love.” Though in this passage Sister Monica speaks for herself, it is a shared sentiment for many who know her.

More than sorrow though, Gammon’s writing explores the hardships endured by deeply fractured individuals who try to do what they know is right, despite their inclinations to do otherwise. This often is represented in passages where Anita, Tomas, and especially Cruz Garcia battle their inward sexual desires, as if letting them out, as Anita does, would expose a buried self that would destroy them. It is also present in the attempts made to adopt Anita’s crime by a man who knows the truth.

One of the most engaging aspects of this novel is that, even though it is heavy with language, paragraphs go on for pages or more at times, the most prominent struggle its characters face is an inability to speak. This damning muteness can be found when Tomas’ lack English prevents his opening up to Anita, “He would tell Cruz about his father, and Cruz would tell Anita; he would tell Cruz about his mother, his brothers and sisters, and Cruz would repeat it…” and more frequently when characters are unable to share what is in their hearts as when Anita struggles to confess to Tomas, “She wanted to tell him, to tell him.” This paradox of characters unable to speak truly in a novel so intense with language heightens both the characters’ fight to exist an honest way, and the readers’ imprint of how inwardly barred each is as he or she attempts to free themselves from the scars on their souls.

Sorrow, like Crime and Punishment, succeeds by raising moral questions it refuses to answer. Simple moralizing is barren when compared to the richness found by exploring characters forced to live through a multitudes of lives no matter how painful.

Fuel for Love by Jeffrey Cyphers Wright

Alexis Rhone Fancher’s Erotic: New and Selected Poems

Chasing Homer by László Krasznahorkai

Eight Perfect Murders by Peter Swanson

The Death of Sitting Bear by N. Scott Momaday

WHILE YOU WERE GONE BY SYBIL BAKER

MY STUNT DOUBLE BY TRAVIS DENTON

Made by Mary by Laura Catherine Brown

THE RAVENMASTER: My Life with the Ravens at the Tower of London

Children of the New World By Alexander Weinstein

Canons by Consensus by Joseph Csicsila

And Then by Donald Breckenridge

Magic City Gospel by Ashley M. Jones

One with the Tiger by Steven Church

The King of White Collar Boxing by David Lawrence

They Were Coming for Him by Berta Vias-Mahou

Verse for the Averse: a Review of Ben Lerner’s The Hatred of Poetry

Ghost/ Landscape by Kristina Marie Darling and John Gallaher

Enchantment Lake by Margi Preus

Diaboliques by Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly

Core of the Sun by Johanna Sinisalo

Maze of Blood by Marly Youmans

Tender the Maker by Christina Hutchkins

Conjuror by Holly Sullivan McClure

Someone's Trying To Find You by Marc Augé

The Four Corners of Palermo by Giuseppe Di Piazza

Now You Have Many Legs to Stand On by Ashley-Elizabeth Best

The Darling by Lorraine M. López

How To Be Drawn by Terrance Hayes

Watershed Days: Adventures (A Little Thorny and Familiar) in the Home Range by Thorpe Moeckel

Demigods on Speedway by Aurelie Sheehan

Wandering Time by Luis Alberto Urrea

Teaching a Man to Unstick His Tail by Ralph Hamilton

Domenica Martinello: The Abject in the Interzones

Control Bird Alt Delete by Alexandria Peary

Twelve Clocks by Julie Sophia Paegle

Love You To a Pulp by C.S. DeWildt

Even Though I Don’t Miss You by Chelsea Martin

Revising The Storm by Geffrey Davis

Nature's Confession by J.L. Morin

Midnight in Siberia by David Greene

Strings Attached by Diane Decillis

Down from the Mountaintop: From Belief to Belonging by Joshua Dolezal

The New Testament by Jericho Brown

You Don't Know Me by James Nolan

Phoning Home: Essays by Jacob M. Appel

Words We Might One Day Say by Holly Karapetkova

The Americans by David Roderick

Put Your Hands In by Chris Hosea

I Think I Am in Friends-Love With You by Yumi Sakugawa

box of blue horses by Lisa Graley

Review of Hilary Plum’s They Dragged Them Through the Streets

American Neolithic by Terence Hawkins

The Sleep of Reason by Morri Creech

The Hush before the Animals Attack by Carol Matos

Regina Derieva, In Memoriam by Frederick Smock

Review of The House Began to Pitch by Kelly Whiddon

Hill William by Scott McClanahan

The Bounteous World by Frederick Smock

Review of The Tide King by Jen Michalski

Going Down by Chris Campanioni

Review of Empire in the Shade of a Grass Blade by Rob Cook

Review of The Day Judge Spencer Learned the Power of Metaphor

Review of The Figure of a Man Being Swallowed by a Fish

Review of Life Cycle Poems by Dena Rash Guzman

Review of Saint X by Kirk Nesset