January 19, 2017

Poetry

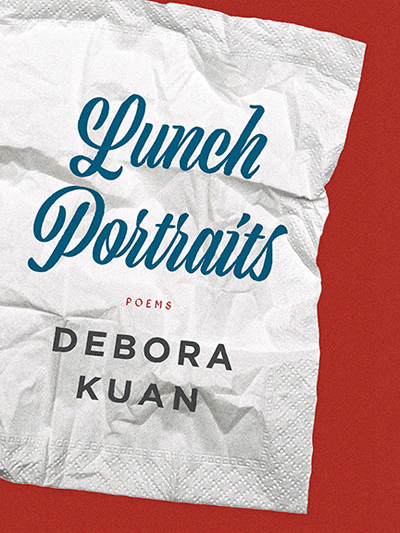

Lunch Poems

by Deborah Kuan

Brooklyn Arts Press, 2016

96 pages

ISBN: 978-1-936767-50-2

by Brennan Burnside

Deborah Kuan’s Lunch Poems works exclusively within the realm of the unwanted. Her poïesis is a diffuse assemblage of matter, her predilections are loose ends and detachedness. Her writing challenges the Bakhtinian notion that poetry is restrictive discourse rooted in a singular voice excluding all others (a centripetal gesture that Bakhtin calls monoglossia and compares to the subversive freedom of many voices – heteroglossia – that he finds most fertile in novels.) Kuan’s poems though refuse even the gesture of an organization into “center” and “margin.” Instead, her work is phenomenological in its devotion to the shape and pattern of the thing being shown without dissipating its purity within analytical intellectualizations. The reader must ontologically shift themselves out of the stalwart discourse of monoglossia and look at what is presented; not hide it in vertical relationships to a mythological paradigm of meaning.

Lunch Poems has three sections that gradually invert the relationship of center to periphery. Beginning with a reorientation of the centralizing mythos of a portrait, moving to amorphous biological meditations reminiscent of (but going far beyond) Richard Grossman’s pastoral work The Animals and finishing with a collage of poetic subjects that fully engage with and are fed by a carnivalesque atmosphere of styles and voices. Appropriate, because as a whole Kuan is creating a collage from and, thereby, an apotheosis of the margin. It’s a task you can visualize if you imagine, for example, removing the centering (and seemingly, essential) gesture of Allen Ginsberg’s mother from his poem “Kaddish.” This is the process Kuan engages in: a loosening from the subject and subsequent exploration of possibilities within the predicate.

Her opening poem, “Automat Prayer” is the last vestige of a traditional center as she gives voice to a washing machine that prays to be acknowledged through commercial intercourse with currency: “Drop a coin in me./I’ll give you a sandwich./You speak burger./I speak pie./Our common tongue/is lunchtime.” The mythos of the periphery is that it supports a centering, deistic mechanism. Western religion relies upon this gesture, but Kuan seeks its subtle undoing. “Portrait Of A Woman With A Hoagie” refuses to separate “Woman” and “Hoagie” into subject and object. The speaker exerts the subject/object gesture of commercial exchange at the poem’s beginning: “I want to drown in six pounds of macaroni salad/The groans of Super Bowl Sunday. The cries of triumph/I want hoagies unfurled from cold foil.” Yet, the image of “Hoagie” subsumes the voice of “Woman.” The image of “Hoagie” rises above vertical relationships to emerge in horizontal equality with divinity: “When God closes one door, somewhere/ He opens a hoagie.” The hoagie eventually causes the transubstantiation of God into the initial subject, “I”, who longs to drown in macaroni salad while watching the Super Bowl. The centering gesture of God becomes lost in the reorientation of “God” and “I” to objects in a periphery where they exist with not against the image of “Hoagie.” This is the gesture Kuan, in several different ways, uses to shift hierarchies so that the mystical obfuscation of their existence is uncovered and explored when seen in a jocular, horizontal relationship.

Kuan further develops this gesture in the second section where the marginal becomes a pastiche that defines and includes the subject, where the subject becomes less of a root and more a diaphanous branch of possible meanings. Her titles repeat the suffix of “Mammal” (“Baby Mammal,” “Teen Mammal,” “American Mammal” etc.) rendering the human in consonance with human creations (“The Clock”) and metaphysical phenomena (“Sui Generis.”) The exercise is especially effective with her poem, “Partridge-Head,” substituting a particular synecdoche for human (“Mammal”) with a piece of an animal (animals, traditionally being considered marginal and dispensable in Western tradition): “I found the partridge one night dead in the middle of the street/... I stuffed and glued him to my helmet and spray-painted the whole thing gold./... I called him “Brother I never had”/...When I dreamed, I dreamed myself weightless.../Now I was lighter than a piano key between city buses./Now I was a pharaoh, swinging my arms into song.” Kuan, by placing a dispensable item (“helmet”) on a marginal object (“partridge”) in the center of discourse reifies it into something eternal (“pharaoh.”) The periphery is an untapped resource flush with life. In consonance with the myriad of unspoken voices within it, the center is broadened and strengthened.

The final section speaks from a myriad of discourses. The subjects in these poems (usually indicated in the title but not necessarily) indicate not a center but a space. In “Seizure,” Kuan uses the image of a cloud, which reappears in several poems in the collection, to indicate a species of being that breaks from centralized discourse to become outside of integrating, centralizing forces of speech and being: “One chemical cloud breaks from the herd./It’s a brain under gas. It’s a gold harp laughing.” Kuan’s “cloud” is a loose end, a disconnection resulting from the rampant forward motion of the herd; the disconnections and subsequent developments occur without the restrictive silencing of a centralizing etiological structure. The resultant being (“gold harp laughing”) develops its own species of eternity.

The space of the cloud encompasses the gesture that Kuan appears to be making: creating space for potential is the only bastion of true being, of life. In that vein, her collection is not just poems working with center and periphery but an etiological suggestion for re-thinking how ontology organizes itself toward rote centering. Perhaps Western perception could benefit from loosening its hold on the center and, to paraphrase Martin Heidegger, allow being to approach one unformed and unobstructed by the past. To revel, in other words, in the infinite potential of the present moment in all its facets.

Fuel for Love by Jeffrey Cyphers Wright

Alexis Rhone Fancher’s Erotic: New and Selected Poems

Chasing Homer by László Krasznahorkai

Eight Perfect Murders by Peter Swanson

The Death of Sitting Bear by N. Scott Momaday

WHILE YOU WERE GONE BY SYBIL BAKER

MY STUNT DOUBLE BY TRAVIS DENTON

Made by Mary by Laura Catherine Brown

THE RAVENMASTER: My Life with the Ravens at the Tower of London

Children of the New World By Alexander Weinstein

Canons by Consensus by Joseph Csicsila

And Then by Donald Breckenridge

Magic City Gospel by Ashley M. Jones

One with the Tiger by Steven Church

The King of White Collar Boxing by David Lawrence

They Were Coming for Him by Berta Vias-Mahou

Verse for the Averse: a Review of Ben Lerner’s The Hatred of Poetry

Ghost/ Landscape by Kristina Marie Darling and John Gallaher

Enchantment Lake by Margi Preus

Diaboliques by Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly

Core of the Sun by Johanna Sinisalo

Maze of Blood by Marly Youmans

Tender the Maker by Christina Hutchkins

Conjuror by Holly Sullivan McClure

Someone's Trying To Find You by Marc Augé

The Four Corners of Palermo by Giuseppe Di Piazza

Now You Have Many Legs to Stand On by Ashley-Elizabeth Best

The Darling by Lorraine M. López

How To Be Drawn by Terrance Hayes

Watershed Days: Adventures (A Little Thorny and Familiar) in the Home Range by Thorpe Moeckel

Demigods on Speedway by Aurelie Sheehan

Wandering Time by Luis Alberto Urrea

Teaching a Man to Unstick His Tail by Ralph Hamilton

Domenica Martinello: The Abject in the Interzones

Control Bird Alt Delete by Alexandria Peary

Twelve Clocks by Julie Sophia Paegle

Love You To a Pulp by C.S. DeWildt

Even Though I Don’t Miss You by Chelsea Martin

Revising The Storm by Geffrey Davis

Midnight in Siberia by David Greene

Strings Attached by Diane Decillis

Down from the Mountaintop: From Belief to Belonging by Joshua Dolezal

The New Testament by Jericho Brown

You Don't Know Me by James Nolan

Phoning Home: Essays by Jacob M. Appel

Words We Might One Day Say by Holly Karapetkova

The Americans by David Roderick

Put Your Hands In by Chris Hosea

I Think I Am in Friends-Love With You by Yumi Sakugawa

box of blue horses by Lisa Graley

Review of Hilary Plum’s They Dragged Them Through the Streets

American Neolithic by Terence Hawkins

The Sleep of Reason by Morri Creech

The Hush before the Animals Attack by Carol Matos

Regina Derieva, In Memoriam by Frederick Smock

Review of The House Began to Pitch by Kelly Whiddon

Hill William by Scott McClanahan

The Bounteous World by Frederick Smock

Review of The Tide King by Jen Michalski

Going Down by Chris Campanioni

Review of Empire in the Shade of a Grass Blade by Rob Cook

Review of The Day Judge Spencer Learned the Power of Metaphor

Review of The Figure of a Man Being Swallowed by a Fish

Review of Life Cycle Poems by Dena Rash Guzman

Review of Saint X by Kirk Nesset